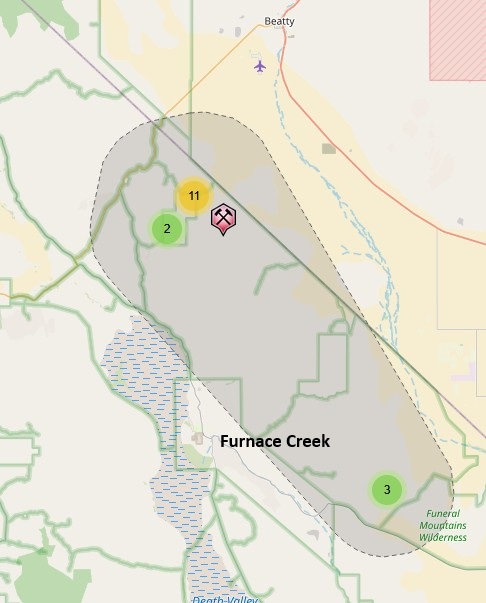

The South Bullfrog Mining District, was also known as the Chloride Cliff Mining District.

Map of the South Bullfrog Mining District, from mindat.org, 2025.

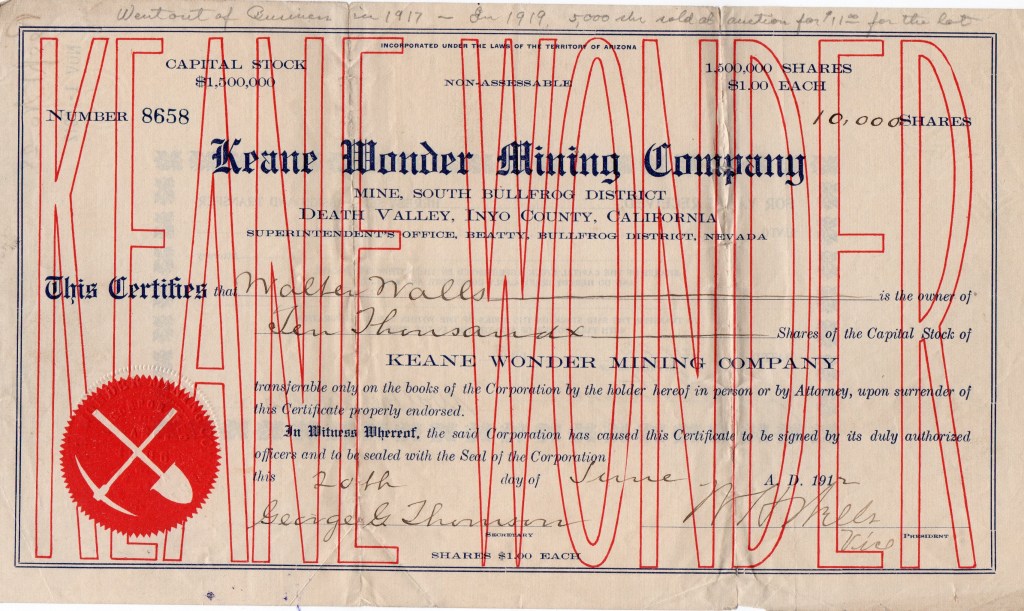

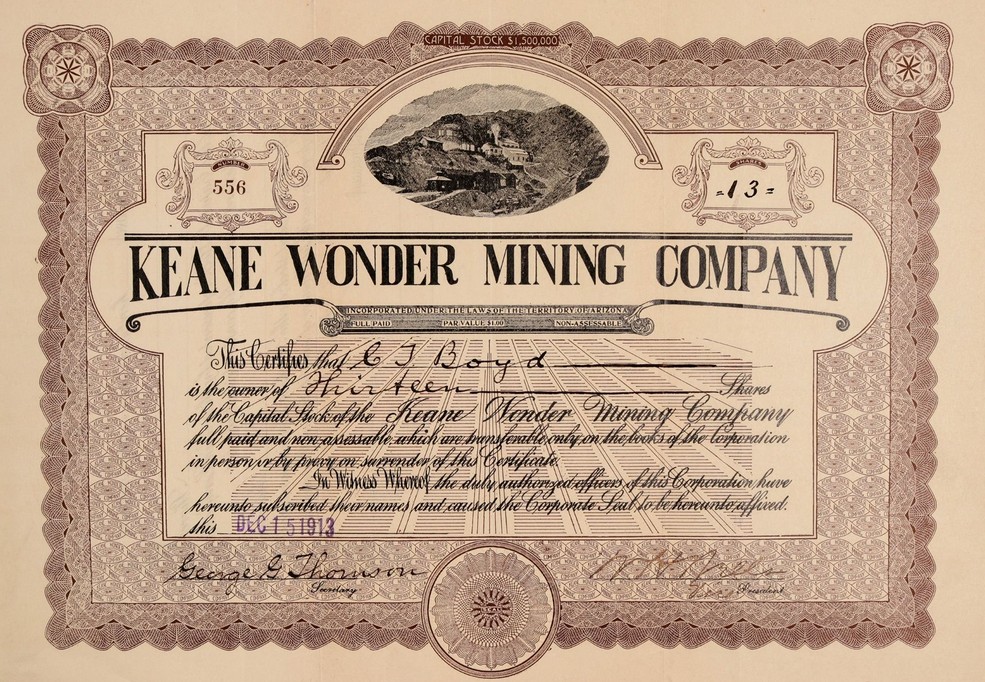

The Keane Wonder Mining Company

Certificate No. 8658, Ten Thousand Shares to Walter Walls, June 20, 1912; George G. Thomson, Secretary, N. H. Wells, Vice President.

Certificate No. 560, Thirteen Shares to C. J. Boyd, December 15, 1913. George G. Thomson, Secretary; N. H. Wells, Vice President.

In December 1904, Irish immigrant miner Jack Keane, and Domingo Etcharren, a Basque butcher from Ballarat, were prospecting for silver in the Funeral Mountains when they found a rich ledge of free-milling gold ore. The site was dubbed “Keane’s Wonder”, and quickly drew attention. The claim was bonded to Captain Jack R. DeLamar for $10,000, with an option to buy for $150,000 — which DeLamar ultimately declined.

In 1906, John F. Campbell and backers bought the mine for $250,000. But the San Francisco earthquake and fire that year wiped out Campbell’s fortune, forcing a sale to Homer Wilson, a seasoned miner from California’s Mother Lode region.

Wilson’s company overcame the logistical nightmare of remote canyons and searing heat to construct a 20-stamp mill and a 2.5-mile aerial tramway. Completed in October 1907, this infrastructure slashed ore-processing costs and unlocked deeper, more profitable gold veins.

By 1912, the richest veins were exhausted and Wilson sold the mine, which was operated intermittently by various owners. The Keane Wonder was one of the most successful Death Valley gold mines. The U.S. Geological Survey reports that the mine yielded somewhere between 30,250 and 33,000 ounces of gold.

The Death Valley Lone Star Mining Co.

Certificate No. 201, One Thousand Shares to M. A. Crocker, September 4, 1906. F. P. Kerns, Secretary; S. (Sam) R. Phail, President.

The first claims of the Lone Star group were located in the summer of 1904, shortly after the Keane Wonder strike. Six claims adjoined the Keane Wonder Mine to the south, with the Bonanza claim being the most promising. The Death Valley Lone Star Mining Company, owning the Bonanza, was organized December 1905.

In early 1906, the company began work on its claims. Small strikes assayed as high as $153 per ton. However, the few high-value veins quickly played-out.

Company president Sam Phail tried all the usual tricks to publicize his mine, such as bringing in specimen ore for display at the Southern Hotel in Rhyolite. But despite his efforts, and the listing of Lone Star on the San Francisco, Goldfield and Rhyolite stock exchanges, interest in the mine never developed. The Rhyolite newspapers never reported any trading of Death Valley Lone Star stock. Towards the fall of 1906, work at the mine was stopped. In July 1907, the company was booted from the San Francisco Exchange for not paying its annual dues.

Although the company performed annual assessment work, by January 1912 the Rhyolite Herald reported that, “no work has been started, nor does it appear that any is in contemplation on the Lone Star property.” The Death Valley Lone Star did not make the transformation from a promising prospect to an actual mine.

Death Valley Big Bell Mining Company

Certificate No. 645, Unissued.

Advertisement, Rhyolite Herald, December 14, 1906

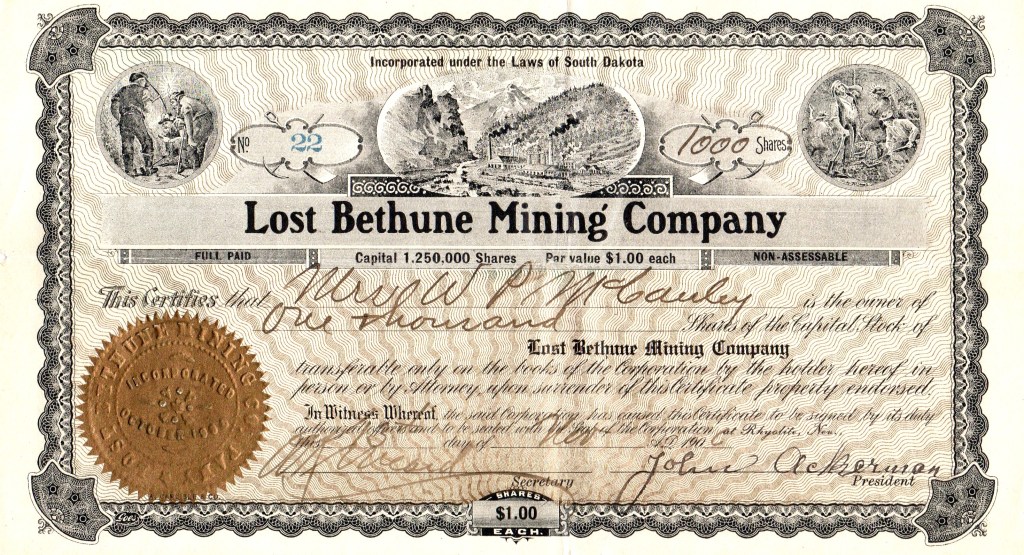

Lost Bethune Mining Company

Certificate No. 22. One Thousand Shares to Mrs. W. P. McCauley, November 13, 1906. [Illegible], Secretary; John Ackerman, President.

Lawrence Bethune was a prospector known from Butte to Colorado to Tonopah to Bullfrog to Randsburg. He was known as “Judge” (or maybe “Colonel”) Bethune, although it was unlikely, he ever sat on a courtroom bench. In 1901, he discovered a silver and copper outcropping near Ibex Spring at the south end of the Funeral Range. Due to the remoteness, Bethune did little more than the annual assessment work to hold the claim.

Bethune’s greatest note of fame arose in tragedy. Earle C. Weller, John Mullan, and Edgar Morris Titus, namesake of Titus Canyon, went missing in Death Valley in June 1905 while traveling from Rhyolite to the Panamints. They got lost in the Grapevine Mountains and ran out of water. On June 26th, Titus left camp to search for a spring and was never seen again. Then Weller set off in search of Titus. Weller never returned.

On July 1, 1905, three men, or more precisely, two bodies and a man barely alive, were found at the north end of Death Valley. The survivor lasted only a short time before succumbing. The three had shed their clothing in their delirium of thirst so there was no way to identify them. They were buried where they were found. Mullan, who had remained in camp, was found in a stupor, returned to Rhyolite, and survived.

When one of Bethune’s burros later wandered into the Grapevine Ranch, it indicated that his body was one of those found weeks earlier. It was assumed that Bethune was heading to his claim when he happened upon Titus and Weller, became exhausted trying to help them, and died.

In April 1906, a headless, animal-mangled body was found in Death Valley with documents that suggested it was Judge Bethune. The head, which was found a short distance away, had been severed by sharp animal fangs.

Nevertheless, even before Bethune’s presumed body was found, an eager bunch of promoters led by A. G. Cushman of Rhyolite, relocated Bethune’s claim as the Lost Bethune Mine. They formed the Lost Bethune Mining Company and started pushing 1.25 million shares with a string of stories about the tragic fate of its discoverer. They stretched the stories a little more with each telling. In 1907, according to Cushman:

“We found the lost Bethune mine about two years ago, but it had been worked for hundreds of years before we found it…Colonel Bethune came into this country some years ago looking for the Breyfogle mine and came out with some fine samples. He returned and loaded his burros with the ore and sold it in Reno. Struck with prosperity, the major portion of his next camping outfit was whiskey, and a year later some prospectors found a lone monument on the side of the Funeral range and beside it was the body of a man – Colonel Bethune – with a note in the monument telling of wandering burro and an exhausted water supply. There was a search made for his property, but it was not found until two years ago. By the workings are old arrowheads, stone cooking pots, the remains of buildings that no modern Indian could or no Mormon would build.”

In the end, the Cushman group succeeded in stripping out over $13,000 worth of high-grade ore to help unload the last of the stock before they finally abandoned the mine and their investors.

Advertisement, Los Angeles Herald, April 28, 1907.

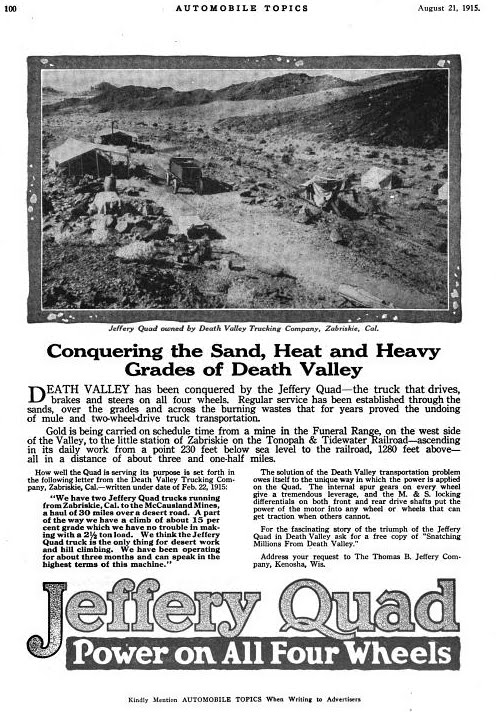

The Ashford Mine…and Death Valley’s First Four-Wheel-Drive Vehicle

The Thomas B. Jeffery Company of California

Certificate No. 11, One Share to C. D. Milburn, April 20, 1915. [?] Kempton, Secretary; C. E. Milburn, President.

In 1907, Harold Ashford re-located what was previously staked by the Keys Gold Mining Company, on the west side of the Funeral Range. The Ashford brother, Henry, Harold, and Louis, alternately worked the mine themselves or leased it to other operators.

The Ashford brothers leased the mine to Benjamin W. McCausland and his son in 1914.

Advertisement for the Jeffery Quad, Mentioning the “McCausland Mines,” Automobile Topics, August 21, 1915.

Advertisement Listing Dealers of the Thomas B. Jeffery Company of California, 1913 Tour Book, California State Automobile Association.