The discovery of Greenwater, as with most throughout the Death Valley area, came about as a result of the Bullfrog boom, sixty-five miles to the north. The great rush to the Bullfrog Hills soon filled up the ground in that vicinity . Late-arriving prospectors were forced to move farther afield. Two such men, Fred Birney and Phil Creasor, ambled south down the east side of the Black Mountain Range, and in February of 1905, while looking for gold, uncovered rich surface croppings of an immense copper belt in Greenwater Valley.

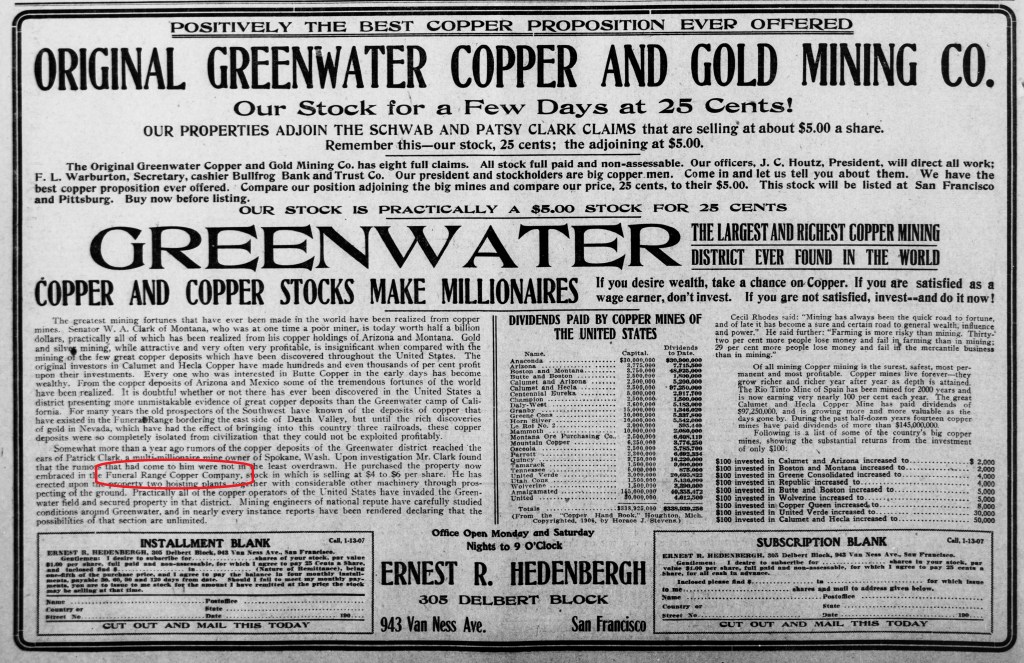

During the short and spectacular Greenwater boom, at least seventy-three known mining companies were incorporated within the district, and literally scores of smaller mines and prospects were opened. The district turned out to be a complete bust, with no ore of consequence ever being mined. None of the seventy-three companies ever entered the production stage of mining, but this is not to say that none of the companies were profitable. Many of the companies which were incorporated for business in Greenwater never actually did any mining at all, nor ever intended to. Indeed, as the Death Valley Chuck-Walla pointed out in several cases, quite a few of the companies did hope to mine the pockets of their gullible investors. The scheme was relatively simple and was quite easy to pull off during the giddy days of the Greenwater boom, for few if any investors in New York or San Francisco could hope to determine which companies were serious and which were fakes. All an unscrupulous operator had to do was incorporate a company with a Greenwater-like name, advertise it as being in the heart of the district or near a well-known mine, and collect the money which started to pour in for stock subscriptions.

The stocks, of course, were worthless, since companies had neither no mining operations, nor intentions of mining, but the promoters would have collected their profits and departed the scene long before this fact became evident.

Nor should we feel too sorry for the investors. Anyone caught up in a boom spirit such as prevailed in Greenwater cannot be pitied for having his dreams fail, for greed was the primary consideration of investors, just as it was for mining promoters. Indeed, investors lost no more money in fraudulent mining schemes than in honest ones, since Greenwater had no productive ores.

As a final note, it should be pointed out that the Greenwater district as a whole was not a fake. Inevitably, considering the rapid rise and fall of the district, which has seldom been paralleled elsewhere, modern writers of western lore have begun to look upon California, they could see booming mining camps. None of these camps had yet reached the peak of their booms when Greenwater started, and as a result the boom spirit of the surrounding territory was at its highest ever. Greenwater, in a sense, was the culmination of that spirit, for only after Greenwater had failed did other camps begin to falter. In short, Greenwater came at a time when all of Nevada was booming, and the times were totally–although unrealistically–optimistic.

In short, there was copper ore at Greenwater. Unfortunately, it did not improve with depth, as it was supposed to have done. The boom at Greenwater eclipsed all others seen before, due to the boom spirit of the times, but it was based upon the contemporary belief that the district held untold riches. Although there were more fraudulent mining companies in Greenwater than in any district we have seen, that was more a result of the unbelievable boom spirit which prevailed throughout the country than of any underlying conspiracy within the district. Greenwater was a real and legitimate mining district, and several companies proved that point beyond all doubt by expending enormous sums of money trying to exploit it. Unfortunately, Greenwater did not have sufficient copper ores to turn it into a producing district.

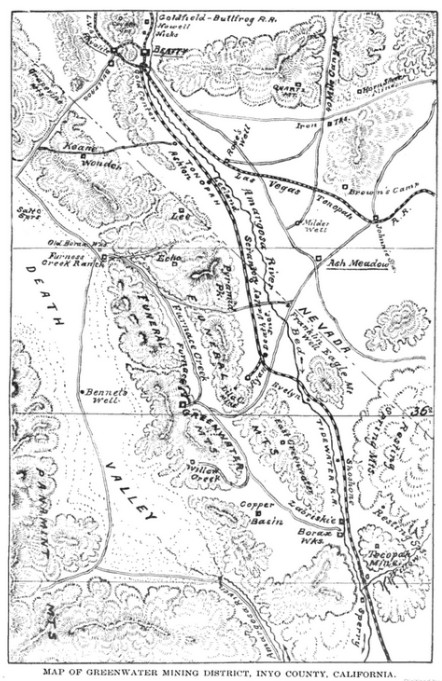

Map of the Greenwater Valley Region, California State Mining Bureau, Bulletin 50, 1908.

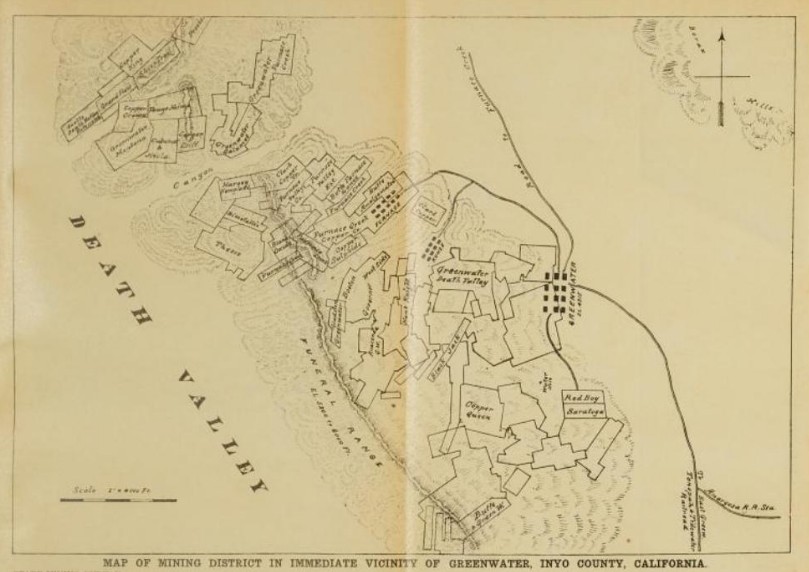

Map of the Greenwater Mining District, California State Mining Bureau, Bulletin 50, 1908.

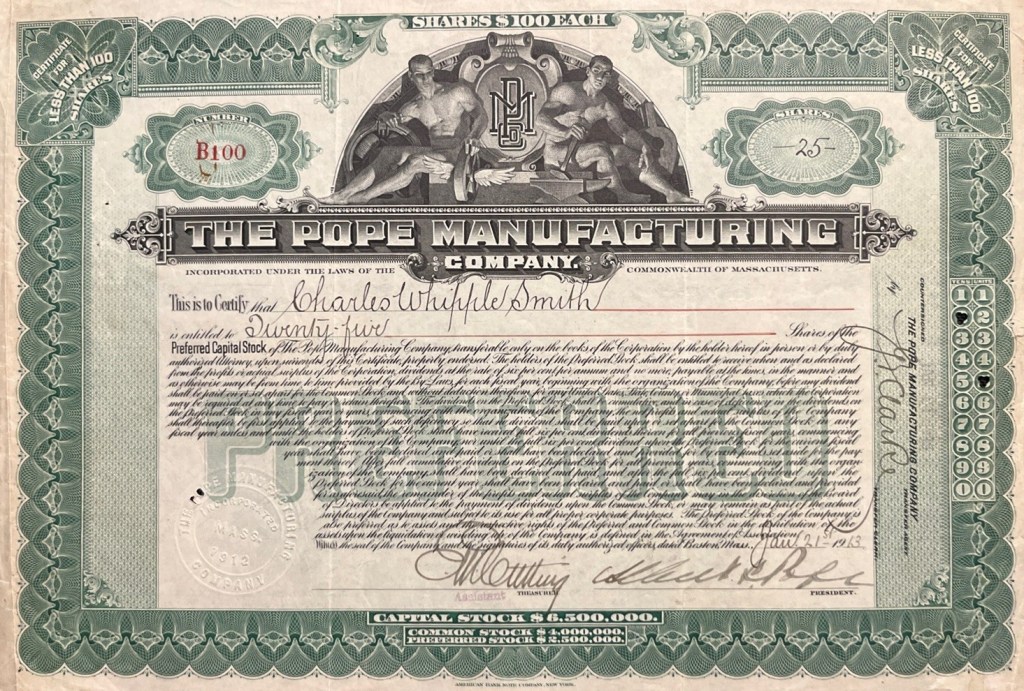

The Pope Manufacturing Company

Preferred Certificate No. B100, Twenty-Five Shares to Charles Whipple Smith, January 21, 1913. E. M. Whettling (?), Assistant Treasurer; Albert A. Pope, President.

Before we review the Greenwater mines, we have to get to Greenwater. Located in Greenwater wash, southeast of Furnace Creek wash, the district was truly in the middle of nowhere, about 40 miles south-southwest of Rhyolite Nevada.

The Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad reached Rhyolite in December 1906, but a traveler might have de-trained at the Amargosa station. The Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad arrived in Rhyolite about the same time, but Zabriskie station, south of Shoshone, California would have been a convenient drop off point.

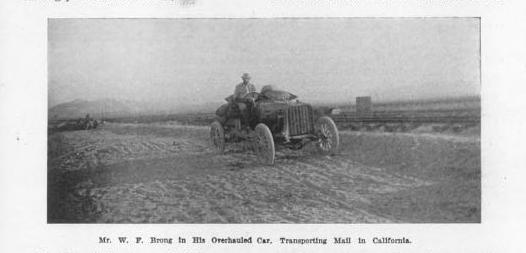

Alkali Bill favored the Pope-Toledo motor car, produced in its namesake city by the Pope Manufacturing Company, for the car’s size and durability.

“Alkali Bill” Brong at the wheel of the Pope-Toledo, with its distinctive flared radiator, Cycle and Automobile Trade Journal, May 1, 1908.

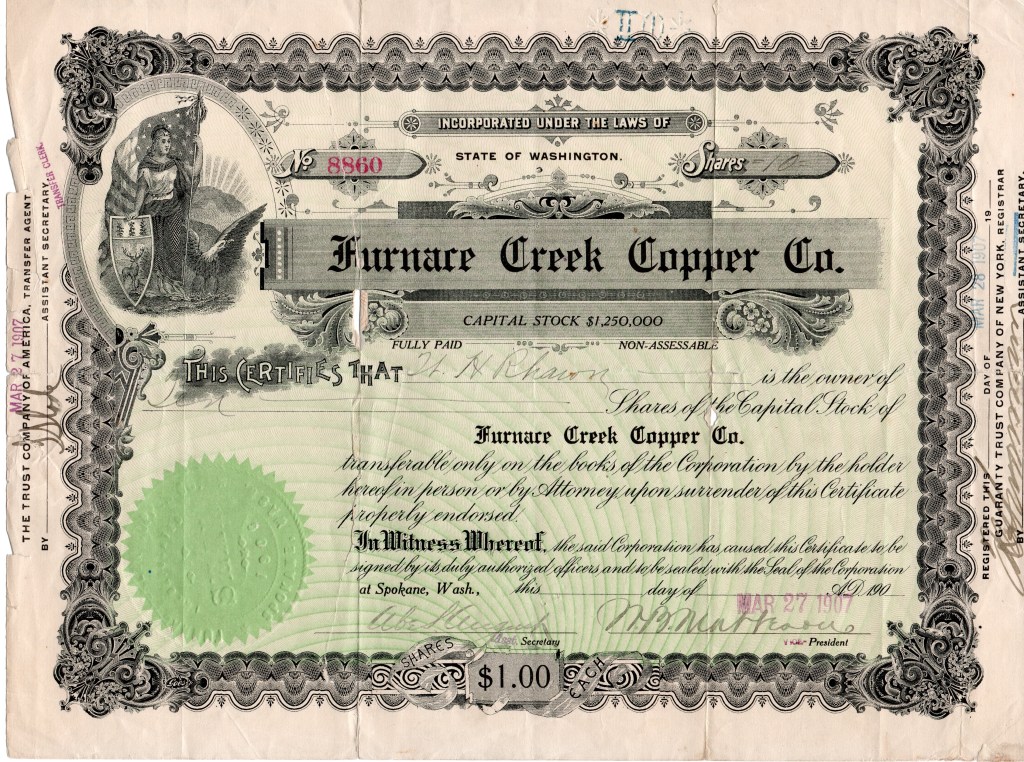

Furnace Creek Copper Company

Certificate No. 8860, Ten Shares to W. H. Rhason, March 27, 1907. Abe S. August, Secretary; W. B. Matteson, Vice President.

Birney and Creasor, the prospectors who discovered copper outcroppings in Greenwater Valley, sent samples of their find to Patsy Clark of Spokane, a well-known copper mining operator, and Clark was sufficiently impressed to buy the claims from the two men in May.

Clark quickly acquired claims, incorporated Furnace Creek Copper Company and began mining operations. By mid-1905, the company had a shaft 35 feet deep, and by March of 1906, although the copper lode had not been found, Clark had decided that the indications warranted permanent and extensive exploration and development. By this time the shaft was sixty feet deep. By mid-April Clark was working two shafts, down to fifty and one hundred feet, respectively. The company’s stock price rose as high as $4.50 a share, a totally unheard-of price for a company which had yet to extract or ship a single pound of ore.

With the money roiling in, Clark began buying up adjacent claims and had soon extended his company’s control to an area of approximately 400 acres. The mine’s shafts reached the 150-foot point in mid-July.

During the summer of 1906, small pockets of high grade ore were occasionally found in Clark’s mine, but no bodies large enough to mine commercially. By mid-August, the shaft was down to 220 feet, then 265 feet by early September, with the stock price hovering around $5.00 per share.

In mid-October, copper ore was struck in a crosscut from the 200-foot level of the main shaft. Development was spurred by the discovery, and by the middle of November, in addition to the numerous crosscuts and drifts which the company was sending out from the 100 and 200-foot levels of its shafts, the main working shaft was still going deeper. By the end of 1906, the company the main shaft was down to 385 feet.

As 1907 opened, work continued on the main shaft, and several other exploratory shafts and cuts were being advanced. By the middle of that month the main shaft had been sunk to 480 feet, another crosscut was started at the 250-foot level. By March 1st, with the shaft at the 500-foot level, new crosscuts were started and ore was discovered. Although the copper deposits uncovered were not large enough to crow about, they were large enough to mine, and the Furnace Creek Copper Company began sacking its best ore for shipment to the smelter. To get there, the ore had to be hauled over fifty miles across the sandy desert to the Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad’s station at Amargosa.

By mid-March, the company was still sacking ore for shipment, and the shaft had been continued below the 500-foot level. Only ore which averaged above 12 percent copper, a very high figure, could be profitably shipped. At the end of that month, the company was still assembling a shipment, which indicates that it did not have a great abundance of 12 percent ore. Nevertheless, with the main shaft down to 550 feet, the Death Valley Chuck-Walla called the Furnace Creek Copper Company the very best mine in the entire Greenwater District.

Sometime in April 1907, the first shipment of ore was sent out, which represented the first shipment from the Greenwater District. The shaft was now down to 600 feet. In mid-May, the first returns reported by the smelter showed that one carload of hand-sorted ore sent cut contained 22.58% copper, which was of profitable level, but two other carloads (of approximately twenty tons each) had not yet been heard from.

Despite these shipments, which represented the closest anyone in the Greenwater District had yet come to becoming a real producing mine, the Death Valley Chuck-Walla noted on June 1st that the company’s position was not looking good. It was running out of development funds. The magazines’ presentments were correct, for shortly after that the mine shut down. The management implied that the shut-down was to avoid the extremely hot weather of the summer months in Greenwater, but everyone knew better, and no one was particularly surprised when the mines were not immediately reopened in the fall. The company scraped together enough money by sales of the remaining treasury stock to continue digging to the 1000-foot level before giving up.

By April 1908 the main shaft was approaching the 800-toot level. Sinking and lateral exploration continued through June, and occasional small pockets of copper ore were found. Although all these pockets soon pinched out, the presence of some ore at these depths was just enough to keep the company’s hopes alive, and it confirmed that the shaft would he sunk to 1000 feet in depth before giving up.

Work continued through the summer. As August approached, the best assessment of the company was that the development results were encouraging, “but nothing out of the ordinary has been reached.” Still the company continued to sink, and steady progress was reported through the fall of 1908, but still without finding any commercial ore bodies.

As 1908 turned into 1909, the work at the Furnace Creek Copper Company became slower and slower, and the company began giving up hope. Finally, in mid-March of 1909, the mine was closed. The Rhyolite Herald sadly announced that the company had “finally given up hope of developing satisfactory ore bodies without going to great depth” and after several years of effort, “work was entirely suspended a few weeks ago.” Miners were discharged and soon even the watchman was given his notice. The elusive ore body, which had been followed sporadically down to 200 feet below the surface, had been completely lost at that point, and although the shaft had been sunk below 800 feet, no more ore had been found.

For a few months, the Furnace Creek Copper Company, held on to its property, waiting to see what would happen at the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company’s property, whose shaft was below 1,000 feet and still advancing. If that shaft hit the copper ore which everyone in Greenwater had been looking for, there was a possibility that the Furnace Creek Copper Company would be able to resume operations. But such did not come to pass, and the Furnace Creek Copper Company mines were abandoned. The entire collection of claims belonging to the company was allowed to lapse, and reverted to county land status in June of 1910, when the company failed to pay $10.51 in Inyo County taxes. As stated in re;ly to a reader’s inquire, Munsey’s Magazine of March 1912, “Property worthless – idle and moribund.”

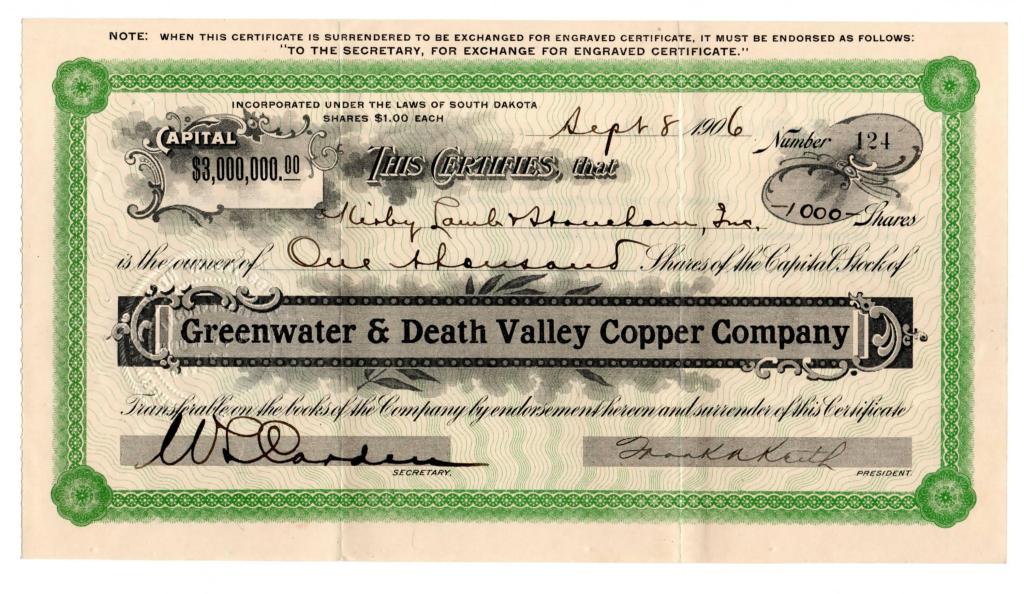

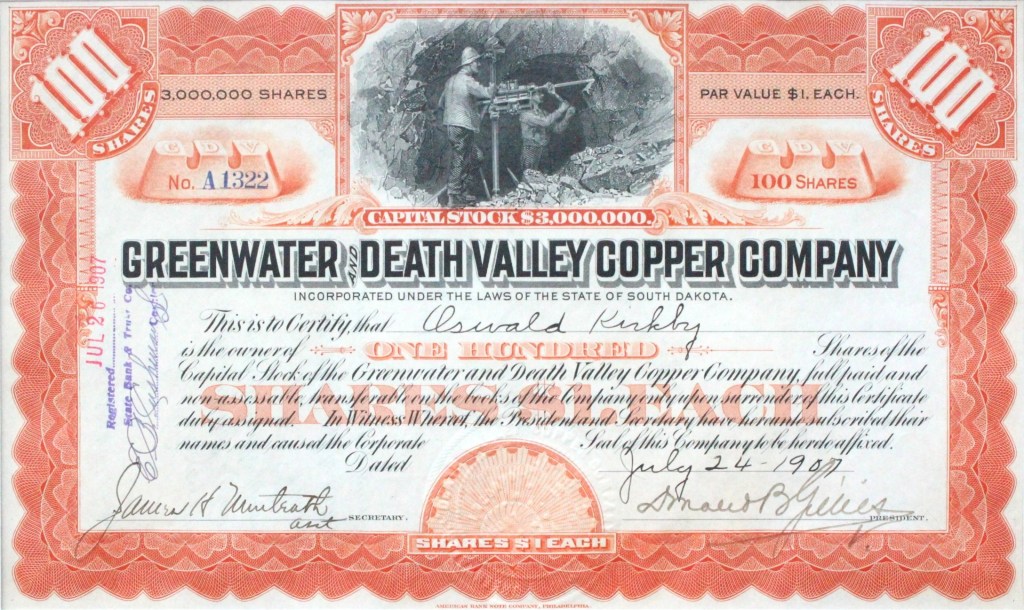

Greenwater & Death Valley Copper Company

Certificate No. 124, One Thousand Share to Kirby Lamb & Stoneham, Inc., September 8, 1906. W. L. Carden, Secretary; Frank Keith, President.

Certificate No. A1323, One Hundred Shares to Oswald Kirkby, July 24, 1907. James H. Newtrath (?), Asst. Secretary; Donald B. Gillies, President.

The other major mining company in the Greenwater district was the Greenwater & Death Valley Copper Company, owned and operated by the great steel industry magnate of the early twentieth century, Charles Schwab. Schwab had been attracted to the gold fields of Tonopah and Goldfield, and dabbled constantly in mines in and around the Bullfrog area. When the Greenwater rush began, Schwab rushed in to capitalize on what seemed to be the biggest boom of them all.

In July of 1906, Schwab began buying up Greenwater mining claims. He paid $180,000 to Arthur Kunze and his partners for a group of sixteen claims. Schwab also purchased water rights at springs in Ash Meadows. On August 10, 1906, the Greenwater & Death Valley Copper Company was incorporated. Schwab retained majority control of the company, even though his name does not appear as a member of the board of directors. The company held 300 acres of ground and announced an extensive development campaign. By the end of August, the main shaft of the mine was down to 100 feet in depth, and work was started on two other shafts. The Bullfrog Miner reported in late September that the company was employing forty miners and the main shaft was down below 100 feet.

The company added a few more claims in early October. Early in November 1906 shipping ore was produced out of one of its shafts. Work continued through the rest of 1906, and by early December two shafts were at the 200-level, and the Greenwater & Death Valley Copper company had emerged as one of the largest operations in the district.

Then, on December 15th, an anticipated merger took place, combining the Greenwater & Death Valley Copper Company, the United Greenwater Copper, and several unincorporated mines owned by John Brock of the Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad, and some Philadelphia financiers.

The new merger company was named the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Mines and Smelting Company, and had a capitalization of $25,000,000, with five million shares worth $5 each. It was easily the largest incorporation that the Death Valley region had ever seen. The new company was a holding corporation, and as such bought up the controlling interests in the companies it took over. The stock distribution in the new company was based upon the amount of stock which had been sold in the older companies, and 68 percent of the merger company’s stock went to buy out the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company, 18 percent to the United Greenwater, and the rest to the owners of the unincorporated mines. Charles Schwab, it was definitely pointed out, was in control of the holding company, and plans were announced for the erection of a smelter at Ash Meadows, where the Greenwater Death Valley Copper Company already had water rights. In addition, the holding company announced that it would build a railroad from the smelter site to the Greenwater mines. A smelting expert was hired for $25,000 per year to supervise the selection of the construction site and the construction of the plant, and hopes were raised that the smelter would be running within a year.

Under the management arrangement of the holding company, however, the subsidiary companies under its control would continue to work on their own, retaining their names, identities and management–subject, of course, to the approval of Schwab and the parent company. Thus the mines continued to explore and develop their own deposits, and the holding company was used for a pooling of resources and capital, which would be necessary in order to finance the capital expenditures which were proposed.

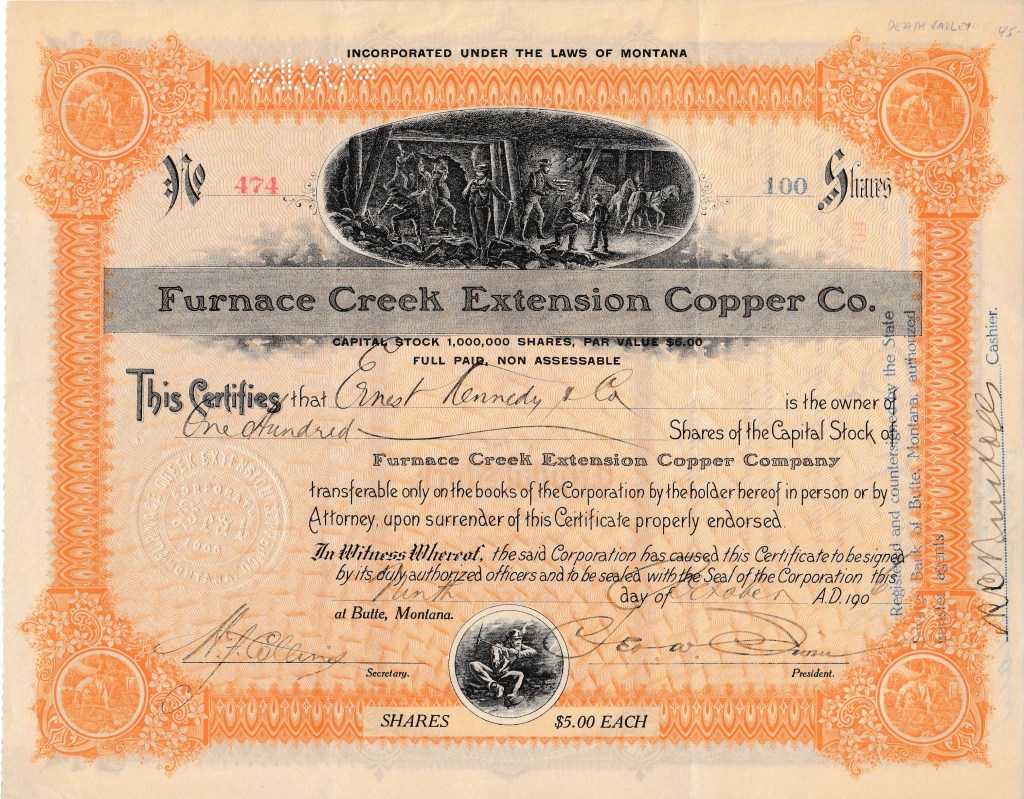

Furnace Creek Extension Copper Company

Certificate No. 474, One Hundred Shares to Ernest Kennedy & Co., October 9, 1906. H. F. Collins, Secretary; Geo. W. Irwin, President.

According to the 1910 edition of The Copper Handbook, “…13 claims, known as the Brady-Kempland group, adjoining the Furnace Creek Copper Co., which have shown a little ore assaying up to 9.5% copper. Idle at last accounts.”

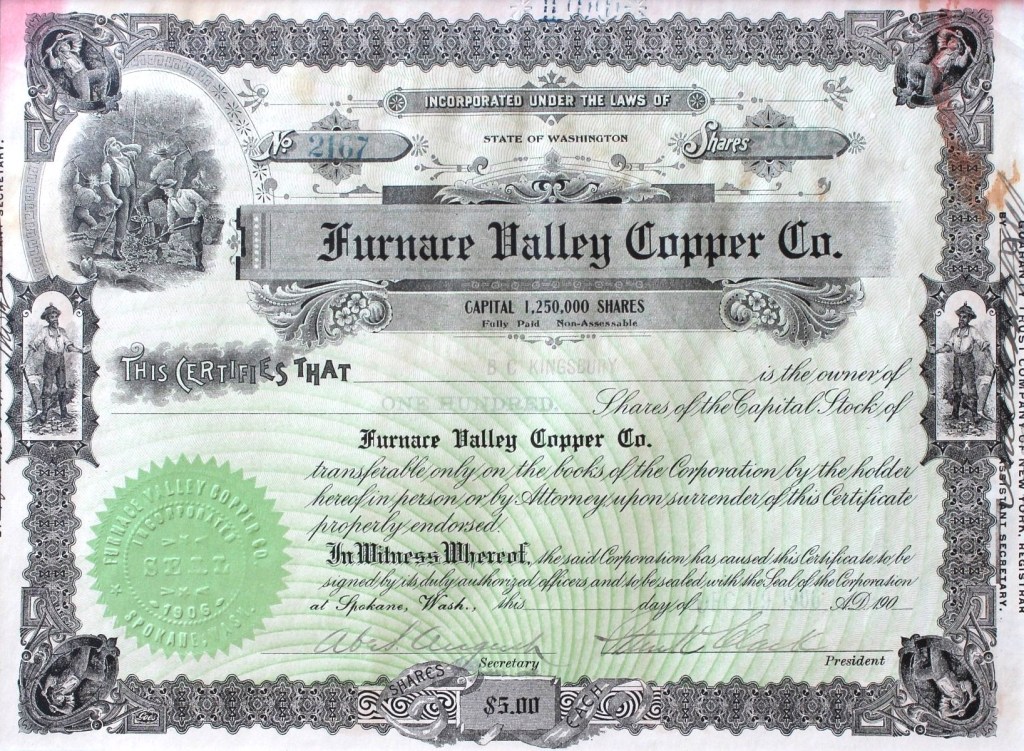

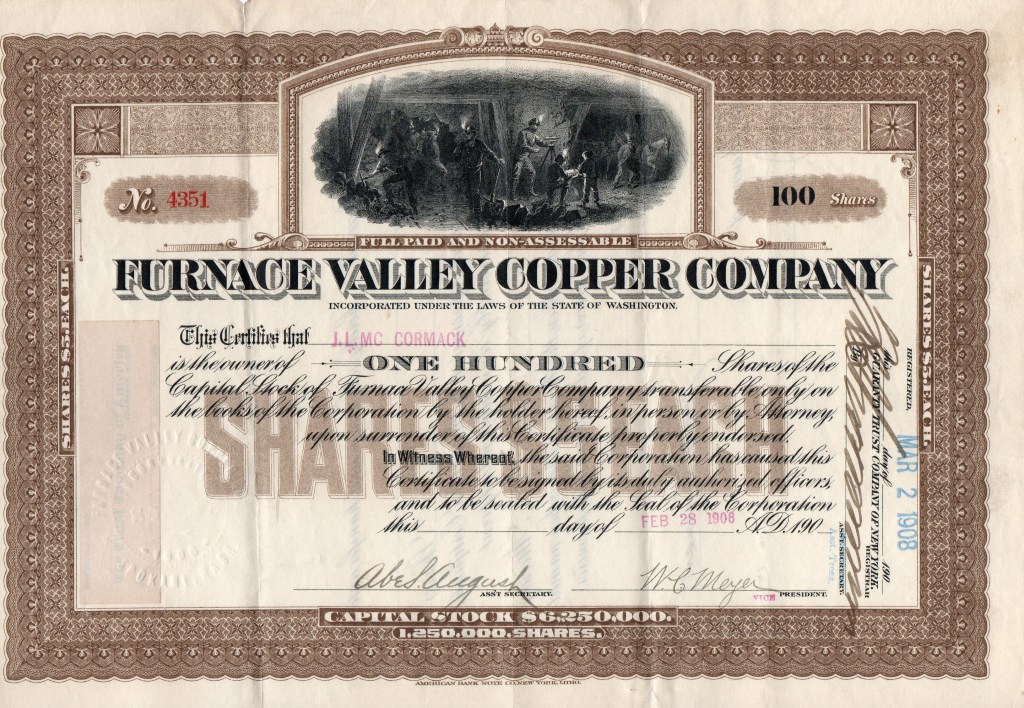

Furnace Valley Copper Company

Certificate No. 2167, One Hundred Shares to B. C. Kingsbury, December 19, 1906; Abe S. August, Asst. Secretary; Patrick Clark, President.

Certificate No. 4351, One Hundred Shares to J. L. McCormack, February 28, 1908. Abe S. August, Asst. Secretary; W. C Meyer, Vice President.

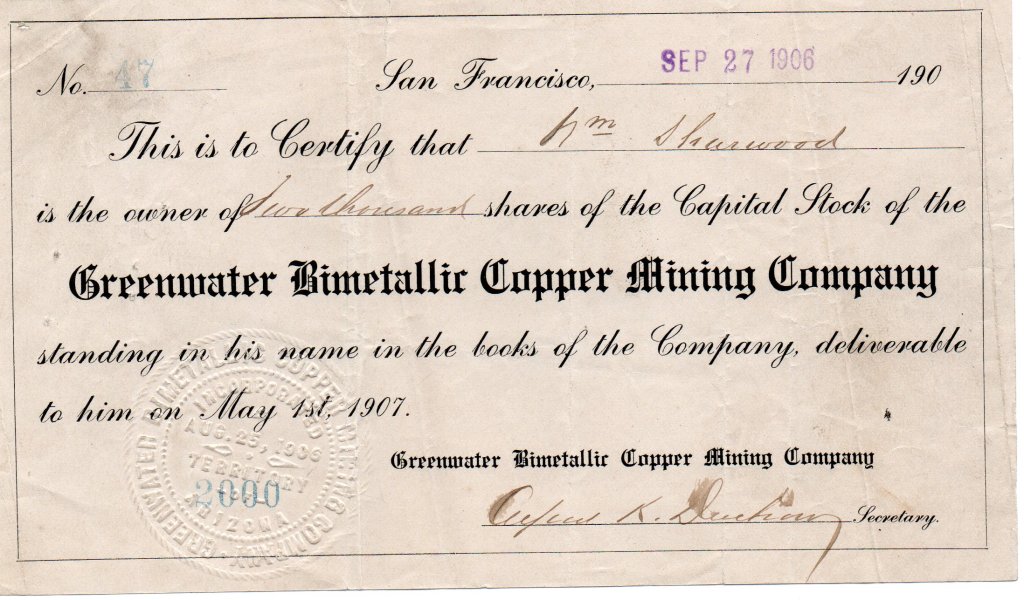

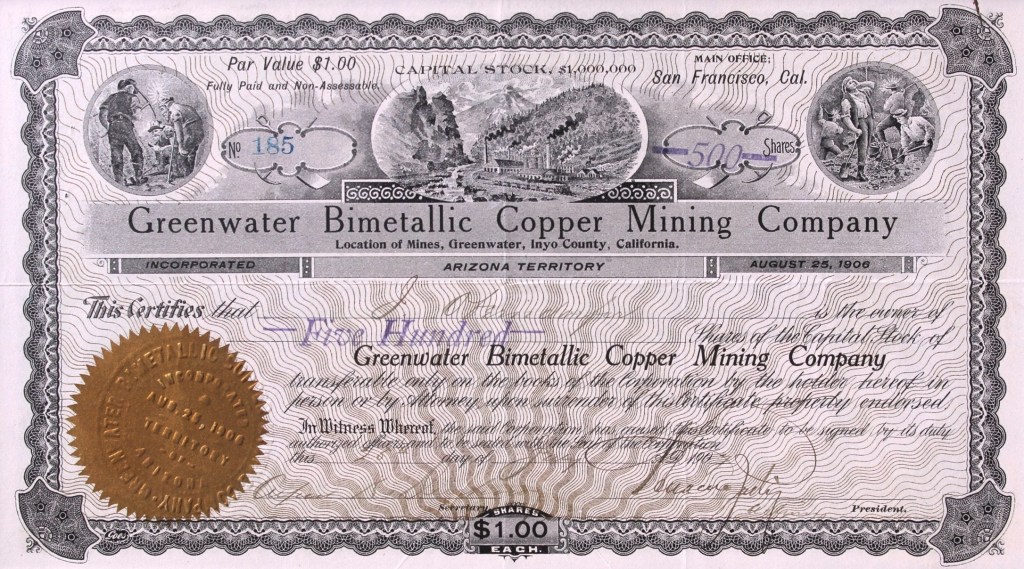

Greenwater Bimetallic Copper Mining Company

Certificate No. 47, Two Thousand Shares to Wm. Sharwood, September 27, 1906. Alfred K. Durbrow, Secretary.

Certificate No. 185, Five Hundred Shares to J. Obendorfer, July 25, 1907. Alfred K. Durbrow, Secretary; [Illegible}, Acting President.

The Greenwater Bimetallic Copper Company was incorporated in Arizona Territory, August 25, 1906, during the Greenwater rush. The company was promoted by Marius Duvall, a Tonopah mining engineer, and had six claims adjoining the Furnace Creek Copper Company’s properties.

In late November 1906, Mr. Duvall visited the property, which was also adjacent to the Greenwater Black Oxide. He reported that the Bimetallic company was driving a tunnel to tap the main vein at a depth of seventy-five feet. Concentrations of subsurface copper were as high as 27%, while surface trenching had exposed concentrations from 3% to 30%.

By 1908, The Copper Handbook reported that Greenwater Bimetallic was idle.

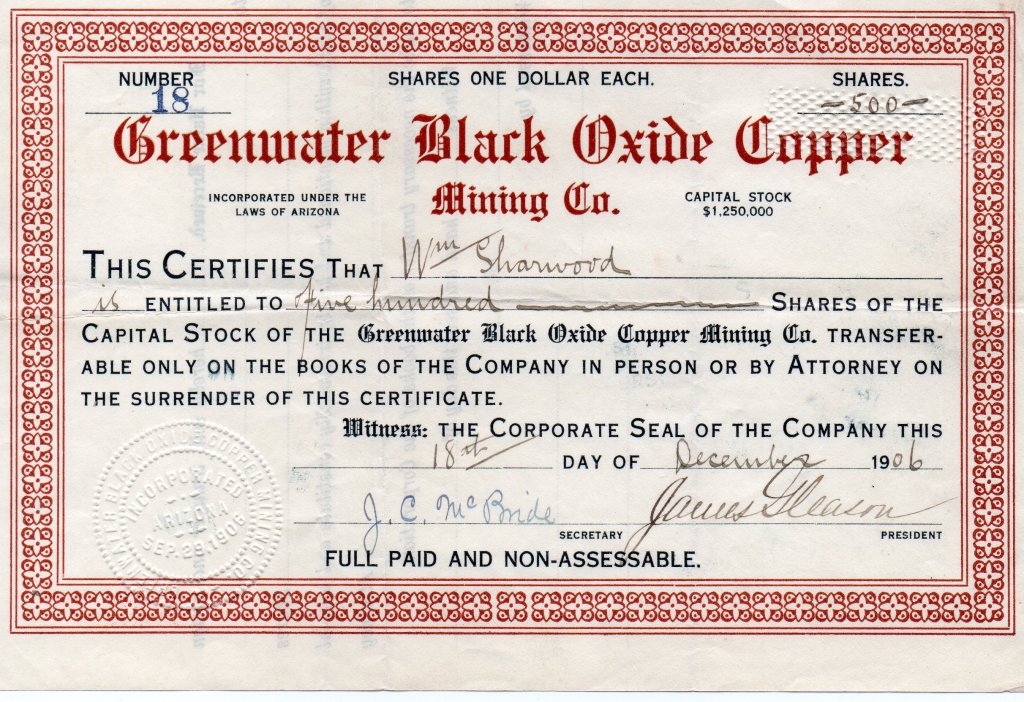

Greenwater Black Oxide Copper Mining Company

Certificate No. 18, Five Hundred Shares to Wm. Sharwood, December 18th, 1906. J. D. McBride, Secretary; James Gleason, President.

The Tonopah Bonanza of November 24, 1906, reported that the Greenwater Black Oxide Copper Mining Company was organized, with nine contiguous claims adjoining the Greenwater Furnace Creek Copper company on the west.

However, according to The Copper Handbook of 1909, the Black Oxide company was reported as “Idle” along with most of the mines of the Greenwater District.

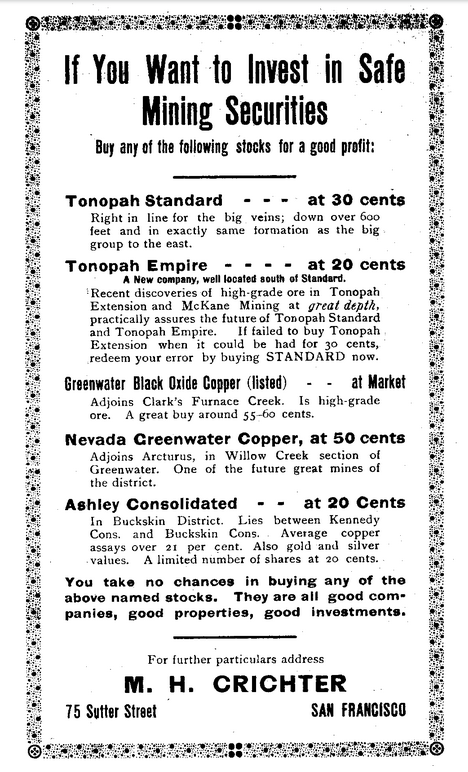

Advertisement, The Homeopathic Annual for 1907.

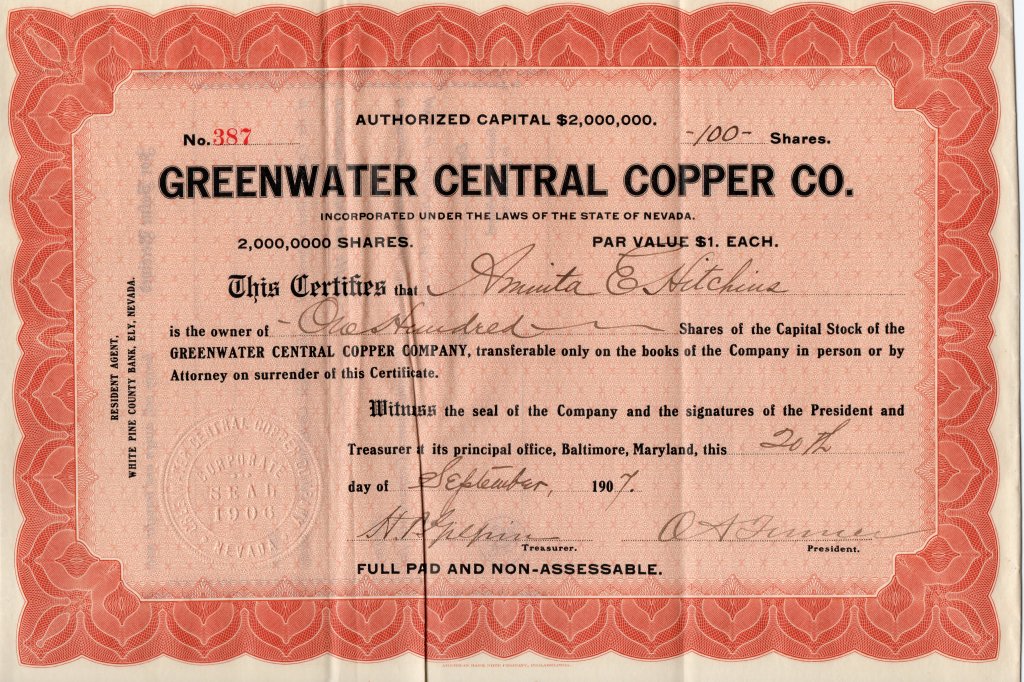

Greenwater Central Copper Company

Certificate No. 387, One Hundred Shares to Aminta E. Hitchins, September 20, 1907. H. (Henry) B. Gilpin, Treasurer; O. (Oscar) A. Turner, President.

The Greenwater Central Copper Company was reported to have lands on “Sheep Creek” in the Greenwater District that, “show a ledge nearly 100 feet wide, carrying a little carbonate copper ore.”

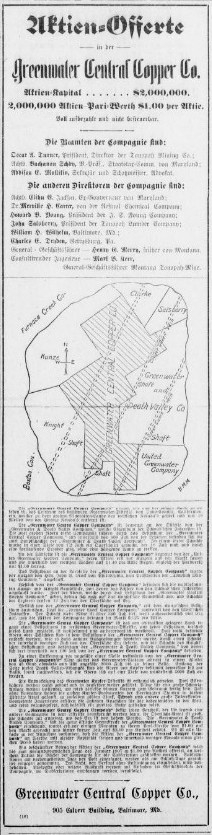

Advertisement, Der Deutsche Correspondent (Baltimore, Maryland) January 18, 1907.

Greenwater Copper King Mining Company

Certificate No. 62, One Hundred Shares to Mrs. Minnie Young, January 23, 1907. C. B. Hollingsworth, Secretary; J. A. Urban, President.

Jack Salisbury may have been known as “The Greenwater Copper King,” but there’s no indication he had a connection to this bit of stockjobbing. Little is known about the Greenwater Copper King Mining Company. It was incorporated in November 1906. The owners had a 100-foot tunnel by April 1907 and extended to 350 feet by October. According to the Tonopah Bonanza, the tunneling was done, “…from the Death Valley Side.” Perhaps, from the western side of Greenwater Valley. No more is known about the Greenwater Copper King Mining Company,

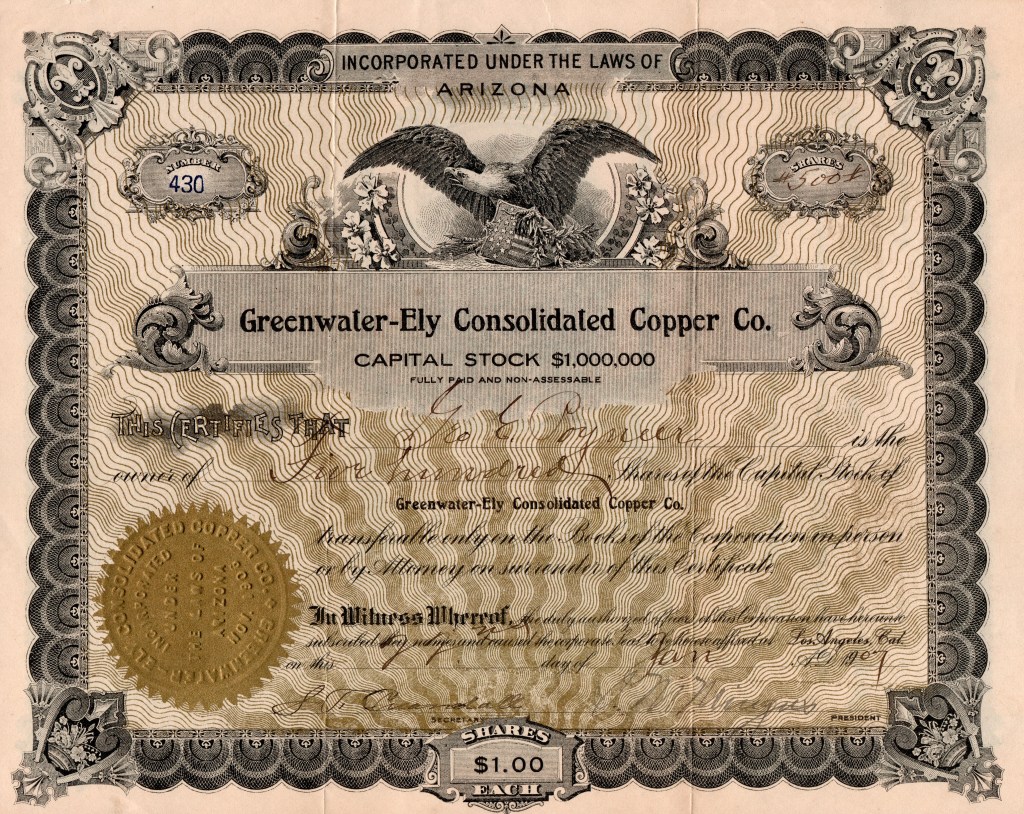

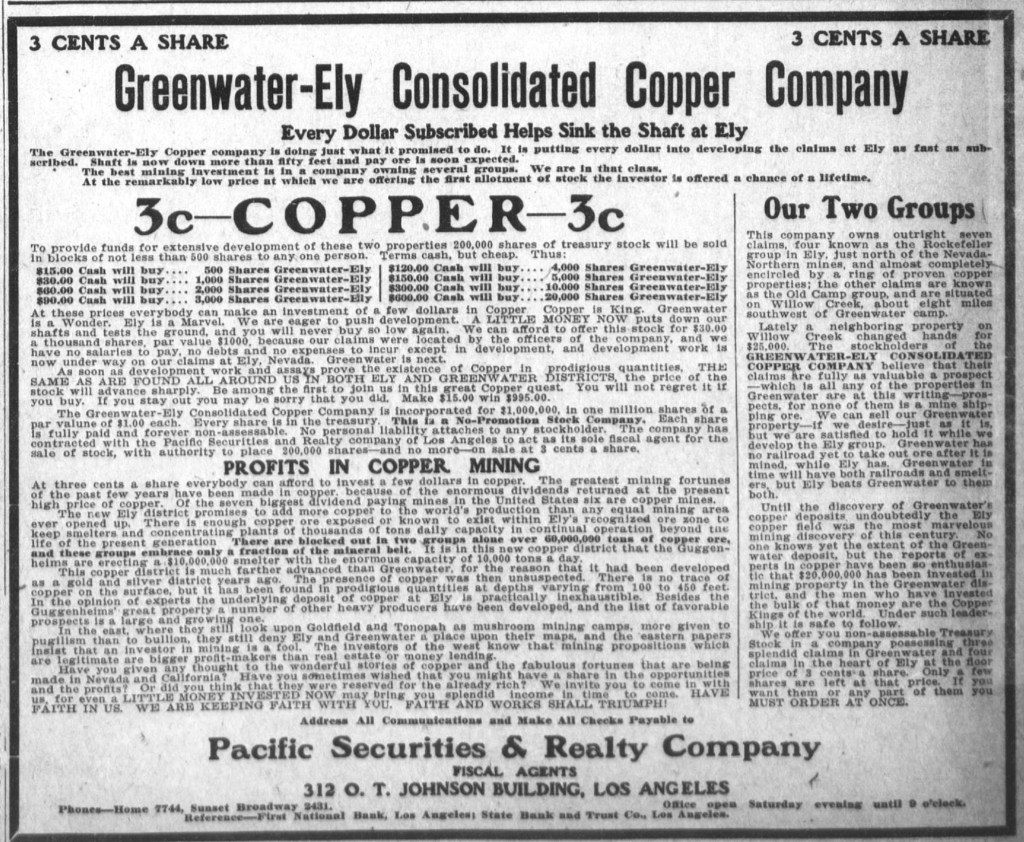

Greenwater-Ely Consolidated Copper Company

Certificate No. 430, Five Hundred Shares to Geo. E. Poyneer, January 22, 1907. S. F. Crandall, Secretary; S. M. Mingus, President.

Like most mining companies with the name “Greenwater” on the stock certificate, the Greenwater-Ely Consolidated Copper Company was just a stock swindle. The company’s worthless Greenwater claims were at Willow Creek, about eight miles southwest of “downtown” Greenwater. As little as Greenwater produced, even less ore came from Willow Creek.

According to the Los Angeles Herald in January 1907, an adjacent claim at Willow Creek changed hands for $25,000. The “Los Angeles stockholders in the Greenwater-Ely believe they have fully as valuable a prospect as that and assert that they could sell out their holdings today for more than they have paid, but they prefer to hold it and develop it themselves.” What the director-stockholders preferred was to bilk unwary investors. As with all Greenwater stocks, mine promotion proved more profitable than any ore.

As early as 1909, The Mines Register indicated that, “No development of importance has been secured … Idle and moribund.” Letters to the company offices in Los Angeles from that journal seeking information were returned as undeliverable.

In 1911, the World Mines Register described the company as, “Dead. Was a mere bit of stockjobbery.” The Engineering and Mining Journal proclaimed that, “Another swindling promoter has come to grief, this time one J. M. Graybill, who has been convicted at Los Angeles of using the mails to promote a fraudulent mining scheme in connection with the Greenwater-Ely Consolidated Copper Company.”

Advertisement, Sunset, January 1907.

Advertisement, Los Angeles Herald, March 17, 1907.

The Consolidated Greenwater Copper Company

Certificate No. 333. One Thousand Shares to Chas. I. Thompson, July 31, 1907. W. (Walter) C. Lamb, Secretary; J. (John) A. Kirby, President.

The June 1907 Death Valley Chuck-Walla described the Consolidated Greenwater as, “The largest single holding in the Greenwater Mining District outside of the Schwab merger property…, which has nearly 500 acres of good copper ground only a short distance southwest of the town of Greenwater…

“The property comprises the Copper Matte group of six claims, the Copper Coin group of eight claim, the Copper Belt group of six claims, the Iron Butte group of five claims and the Copper Coin Fractions Nos. 1, 2, and 3…. The vast extent of the property, however, is the matter which makes it of more than ordinary interest. The ground covered by the company’s locations is sufficient to make half a dozen ordinary mines, and if the indications now seen are correct, the mine will without doubt be one of the richest in the district.”

The Copper Handbook 1909 edition listed the mines of Consolidated Greenwater as, “Idle.”

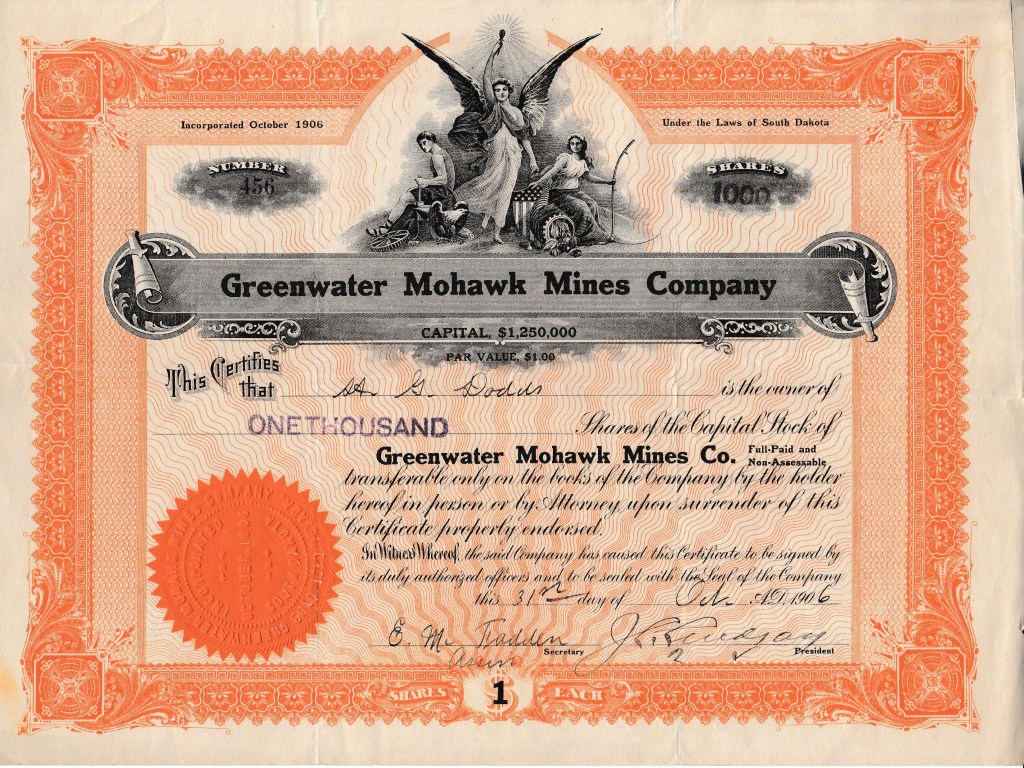

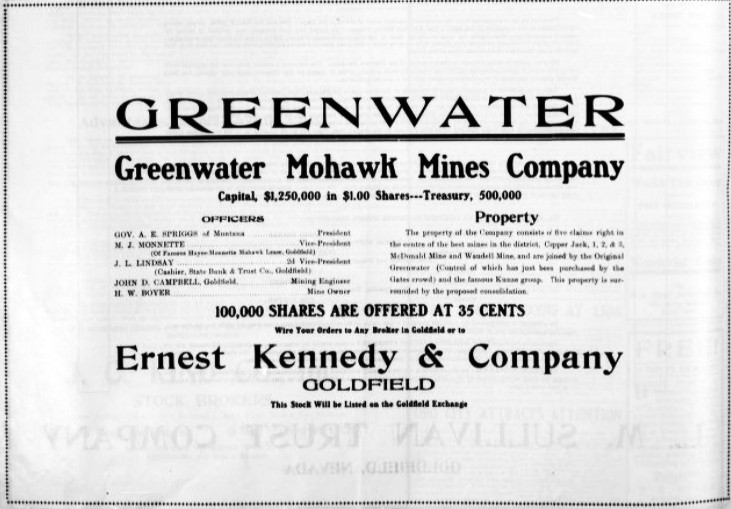

Greenwater Mohawk Mines Company

Greenwater Mohawk Mines Company, Certificate No. 456, One Thousand Shares to H. G. Dodds, October 31, 1906. E. McFadden, Asst. Secretary; J. L. Lindsay, 2nd Vice President.

As reported in the 1910 edition of The Copper Handbook, “Idle and apparently prompted mainly for stock-jobbing purpose notwithstanding the president being a former governor of Montana.”

Advertisement, Goldfield News, October 27, 1906.

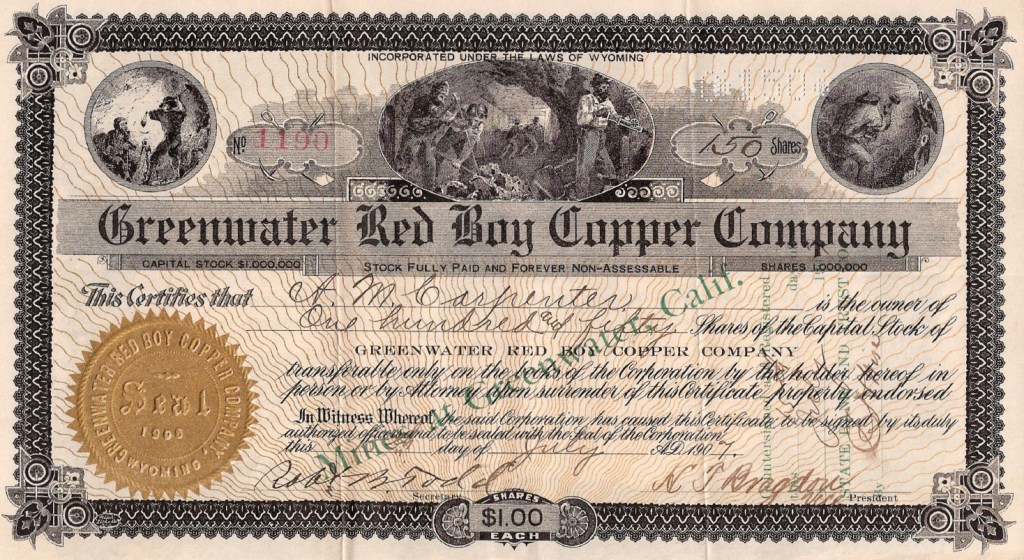

Greenwater Red Boy Copper Company

Certificate No. 1190, One Hundred Fifty Shares to A. M. Carpenter, July 10, 1907. Robt. B. Todd, Secretary; H. T. Bragdon, Vice President.

Greenwater Red Boy was considered to be a twin of the Greenwater-Saratoga Copper Company, with the same officers and directors. The Copper Handbook reported that, “…the company had 5 patented claims covering 100 acres, adjoining the Greenwater & Death Valley Copper Mining Co. on the west. Assays reported up to 28% copper and $66 gold per ton, opened by a 400′ crosscut tunnel and a 600′ shaft. Idle.”

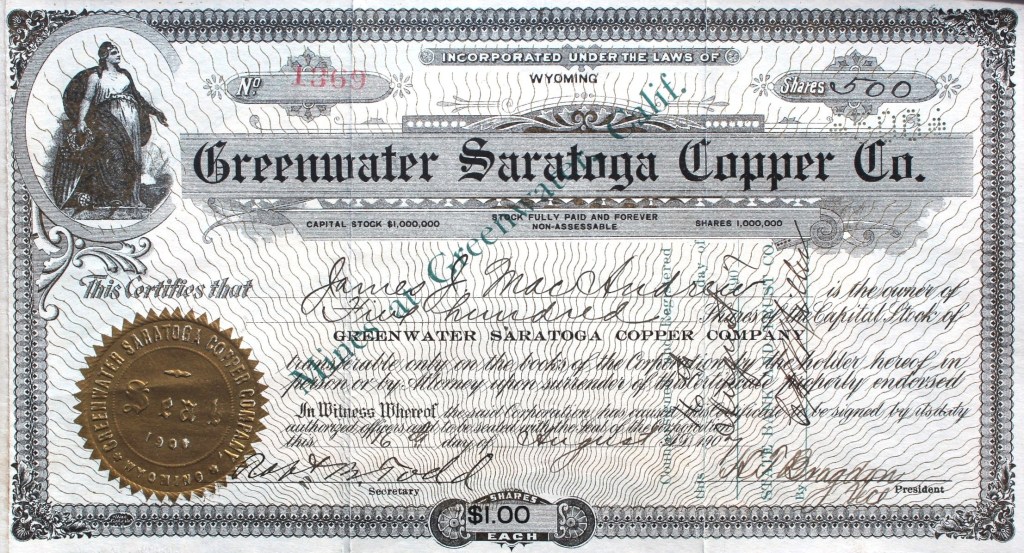

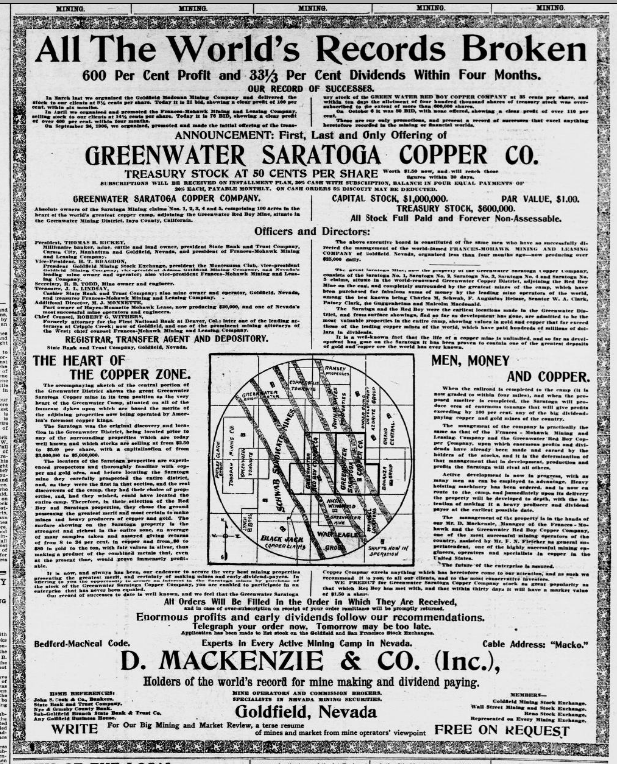

Greenwater Saratoga Copper Company

Certificate No. 1369, Five Hundred Shares to James J. MacAndrews, August 16, 1907. Robt. B. Todd, Secretary; H. T. Bragdon, Vice President.

A “twin” mining company, of and adjacent to the Greenwater Red Boy Copper Company. The Copper Handbook of 1909 reported that, “The mine opened by a 300-foot crosscut and a 550-foot shaft … Idle, put plans sinking and crosscutting, 1n 1909.” Unlikely, as the Greenwater District had already busted.

Advertisement, The Sunday Star (Washington, D.C.), October 14, 1906.

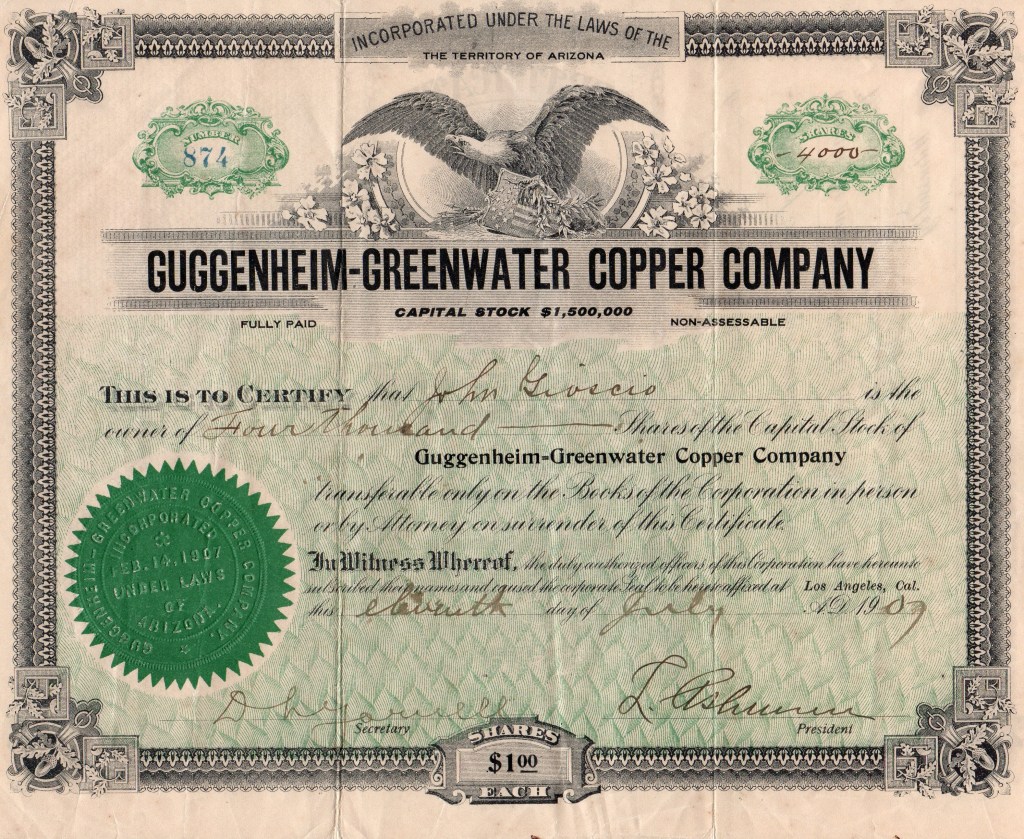

Guggenheim-Greenwater Copper Company

Certificate No. 874, Four Thousand Shares to John Gioscio, July 11, 1907. E. L. Yarnell, Secretary; L. Ashman, President.

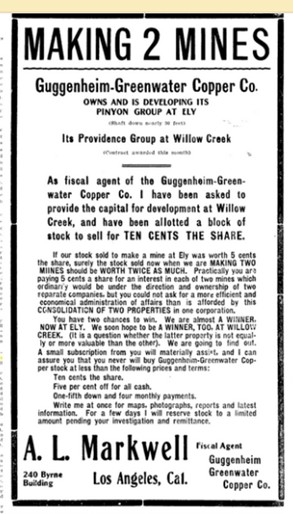

A name, in fact, was all that some companies seemed to offer – in addition to their stock, that is. Such was the Guggenheim – Greenwater Copper Company, a penny a share mail order stock that blatantly advertised, “YOU HAVE HEARD of the Guggenheims … YOU HAVE READ ABOUT Greenwater … BUY INTO BOTH.” In truth you got neither. The famous Guggenheim family had nothing to do with this company, and the claims (not mines) were at Ely, Nevada, and Willow Creek, 35 miles south of Greenwater.

The Copper Handbook noted in 1908, “Advertising is flamboyant, and apparently company is merely a stock-jobbing enterprise” and “Idle several years and apparently out of funds and credit.” Somehow, the company continued into at least 1910, when The Mines Directory stated, “Not much work done…at either claim location.”

Advertisement, The Mining Investor, September 2, 1907.

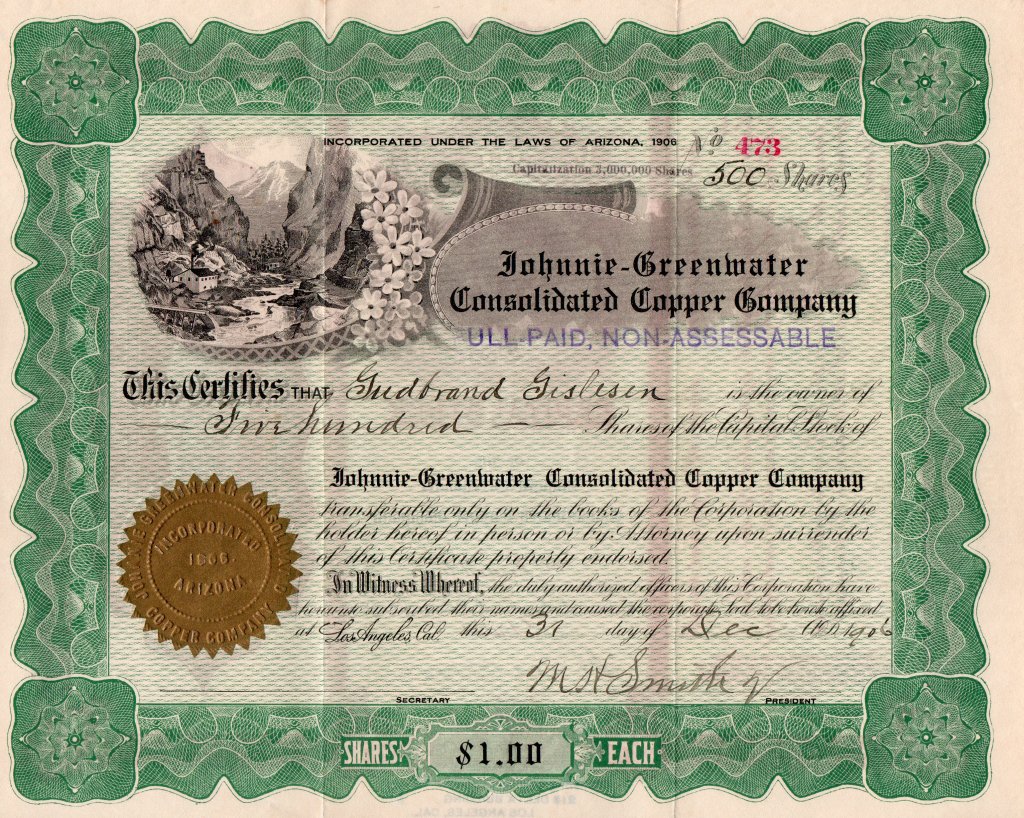

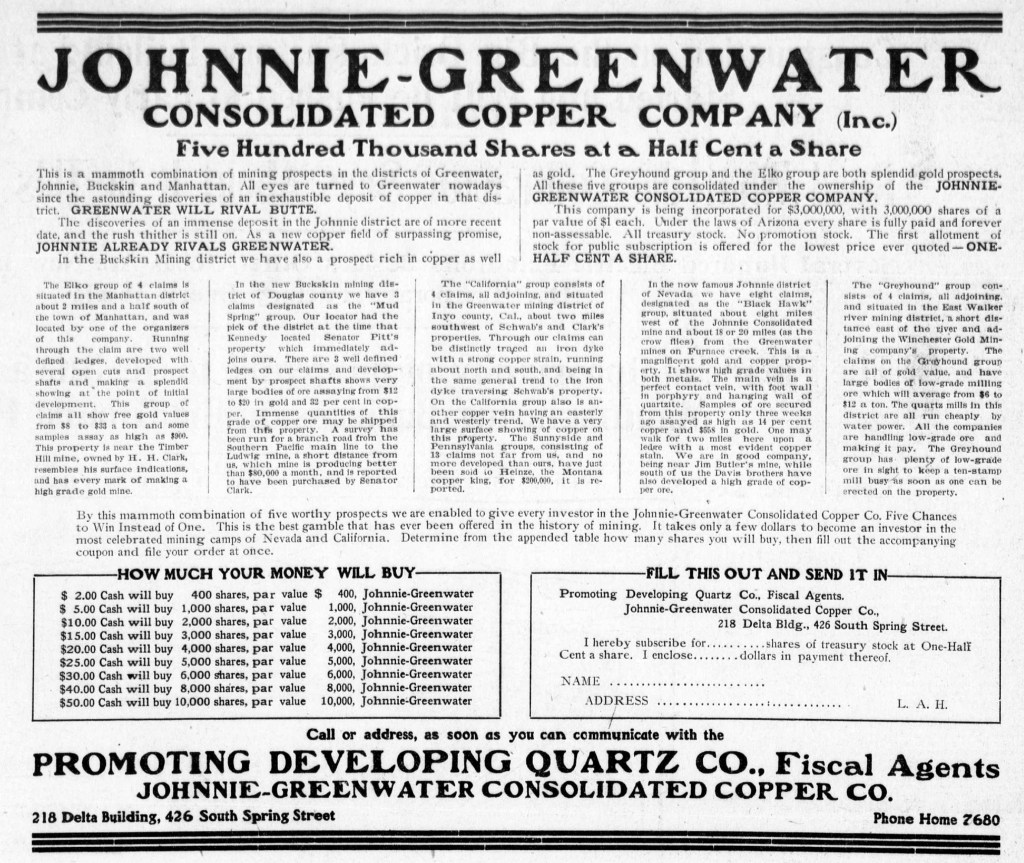

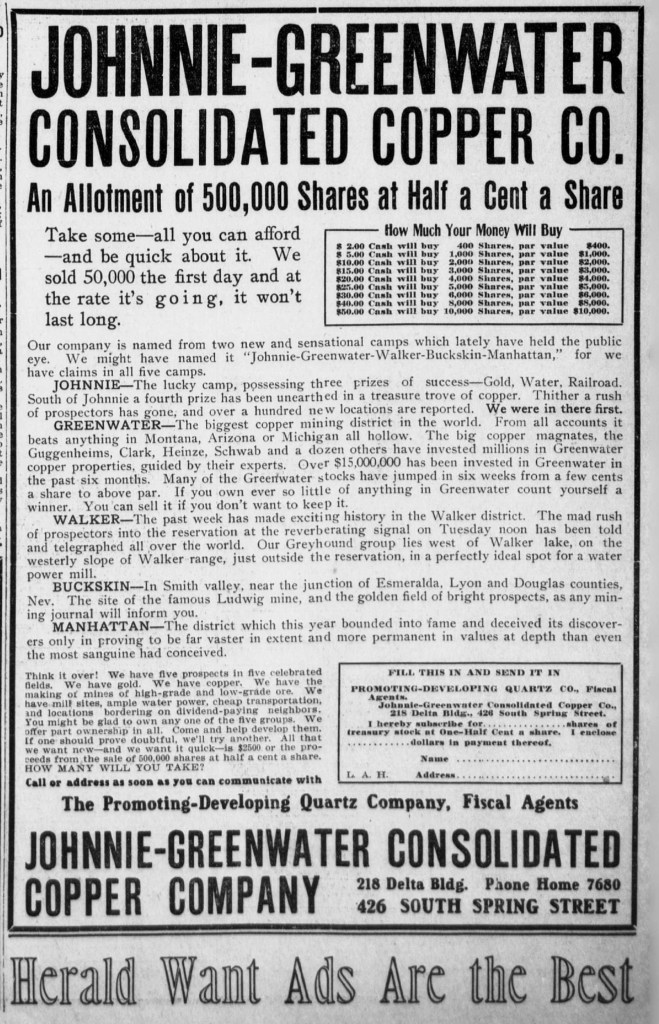

Johnnie-Greenwater Consolidated Copper Company

Certificate No. 473. Five Hundred Shares to Gudbrand Gislesen, December 31, 1906. M. H. Smith, Jr., Vice President.

Another of the many Greenwater companies that mined dollars out of the pockets of the plungers was the Johnnie-Greenwater Consolidated Copper Company. The newspaper advertisement advised prospects, “If you own ever so little of anything at Greenwater count yourself a winner. You can sell it if you don’t want to keep it.” In truth, you were likely a loser that couldn’t sell as Greenwater went bust.

The Johnnie Mining District was located several miles north of Pahrump, Nevada. The district’s mines were somewhat successful gold producers, having a good location only six miles from the Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad. So, why not take the Johnnie name to boost a scam at Greenwater?

According to The Copper Handbook of 1908, the company owned claims at Greenwater, California, and Elko and Johnnie, Nevada. “The Greenwater group, 4 claims, is undeveloped.” Undeveloped the claims likely stayed, as The Copper Handbook of 1911 described the company simply as “Dead” – just like the rest of Greenwater.

Advertisement, Los Angeles Herald, October 28, 1906.

Advertisement, Los Angeles Herald, November 4, 1906.

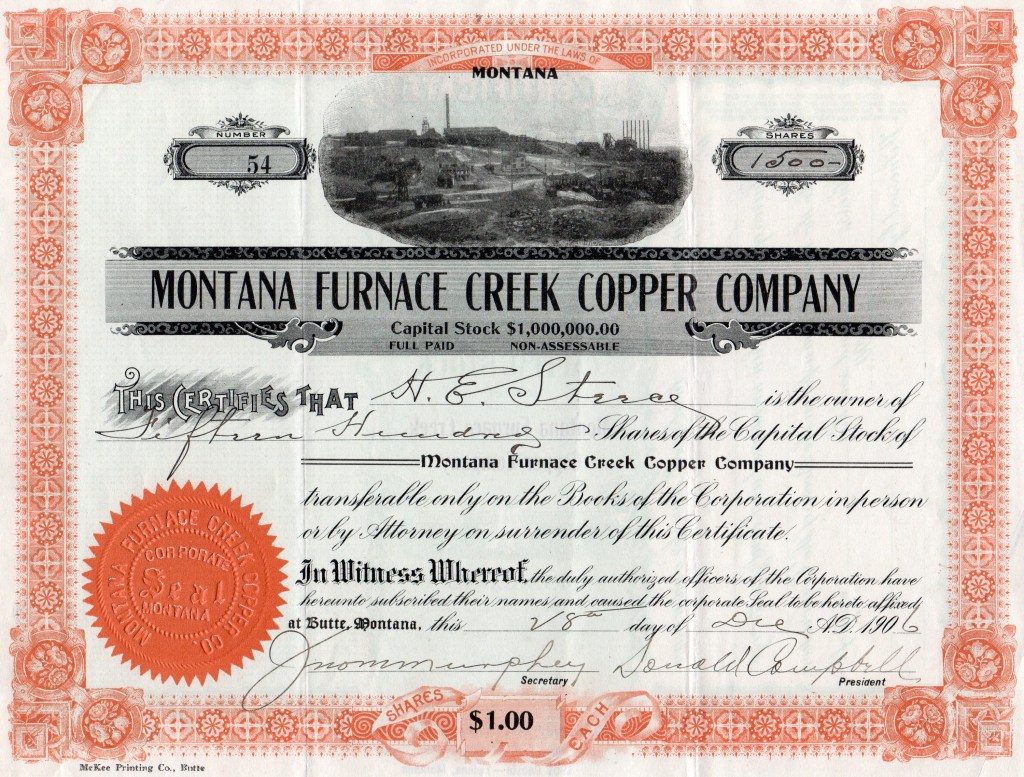

Montana Furnace Creek Copper Company

Certificate No. 54, One Thousand Five Hundred Shares to H. E. Sterce, December 28, 1906. Jno. M. Murphy, Secretary; Donald Campbell, President.

The Montana Furnace Creek Copper Company was a short-lived, speculative concern with a name suggestive of a great copper producer of Butte, Montana. The company was organized in December 1906 to operate eight claims in Greenwater. The company president, Donald Campbell, was a prominent medical doctor, political activist, investor and board member in several mines in Butte. He was the personal physician to the Butte Copper King and early Greenwater investor, Augustus Heinze.

In November 1906, Dr. Campbell traveled to Greenwater to inspect the camp, of which he spoke favorably. The claims were touted in the mining press as containing vein extensions from Patsy Clark’s properties. However, there was no extension of the company’s life beyond November 1907 when the Montana-chartered company failed to pay California’s corporate registration fee.

The Panamint Greenwater Gold and Copper Mining Company

Certificate No. 314, Three Hundred Fifty Shares to C. H. Rankin, Februay25, 1907. Wm. Woodward, Jr., Secretary; C. M. Kittredge, Vice President.

Organized by Denver promoters with the “Panamint” reference to provide a connection to the early Death Valley mining district, this company was one of dozens that cashed-in on the Greenwater rush. The Panamint Greenwater owned three claims at Greenwater and four claims at the Wild Rose and Skidoo districts.

By 1910, most Greenwater mines were described in the mining press with words like, “moribund,” “dead,” and “idle.” The situation of the Panamint Greenwater was, “…assessment work not done, and claims at Greenwater subject to relocation, but nobody wants them…Bares every indication of being a mere bit of Denver stock jobbery,” and bluntly, “Was a Denver swindle.” This is further supported that although the certificate states, “Incorporated Under the Laws of the State of Wyoming,” there is no record of incorporation by the Wyoming Secretary of State.

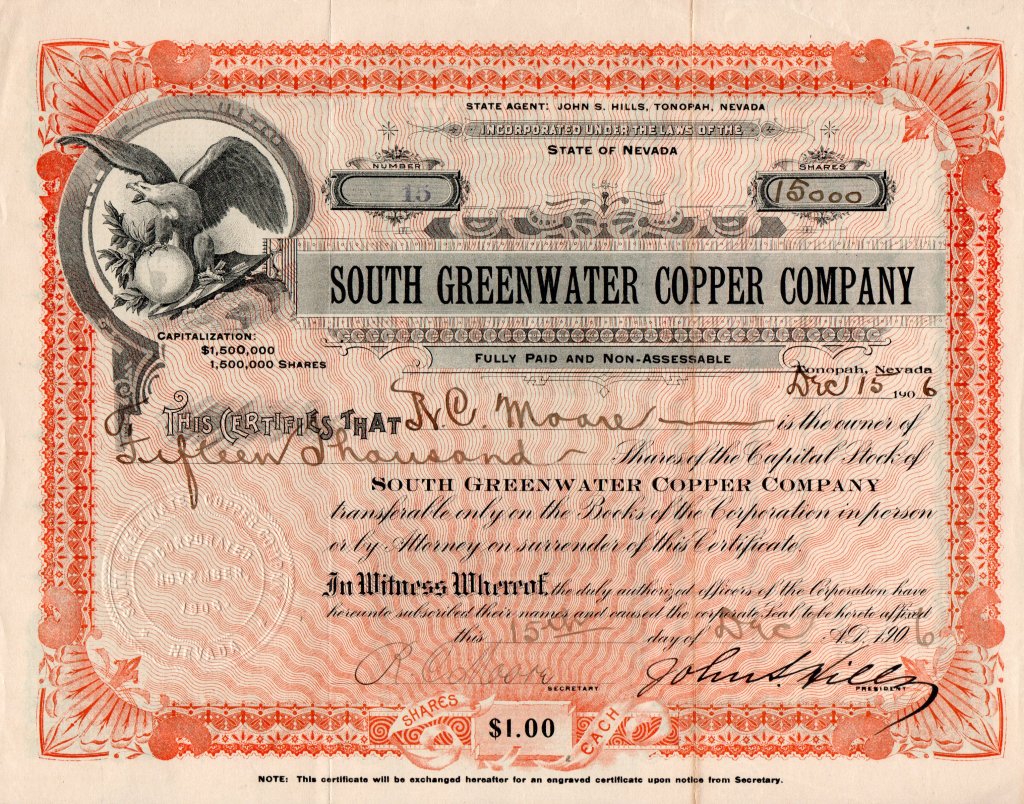

South Greenwater Copper Company

Certificate No. 15, Fifteen Thousand Shares to R. C. Moore, December 15, 1906. R. C. Moore, Secretary; John S. Hills, President.

The South Greenwater Copper Company owned fourteen claims covering an area of 275 acres, about 15-miles south of Greenwater, at Miller Springs. . However, the 1910 edition of The Copper Handbook described the company “promising,” yet “Idle,” along with the rest of Greenwater.

Advertisement, The Goldfield News, January 5, 1907.

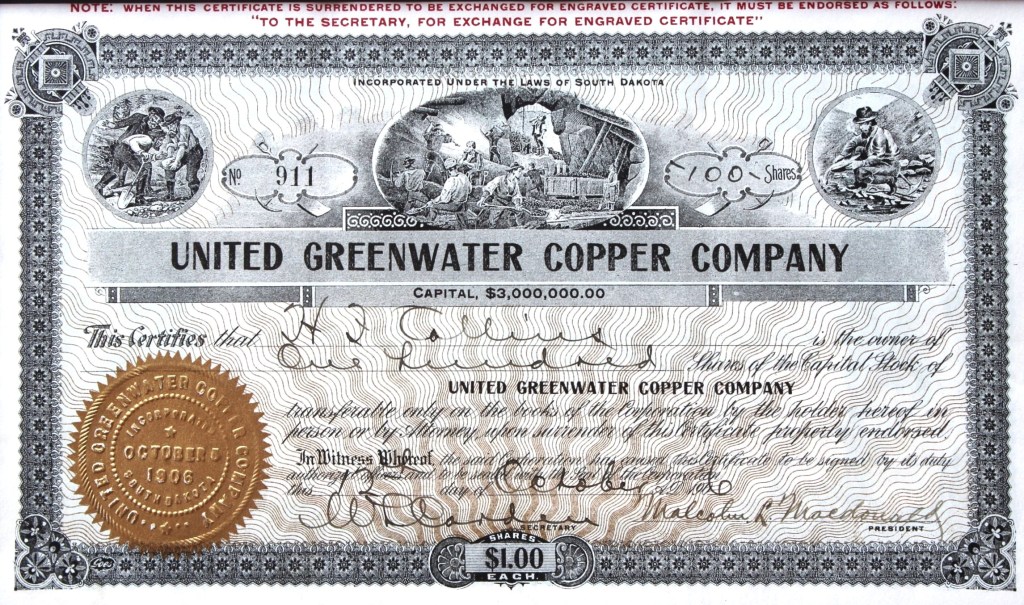

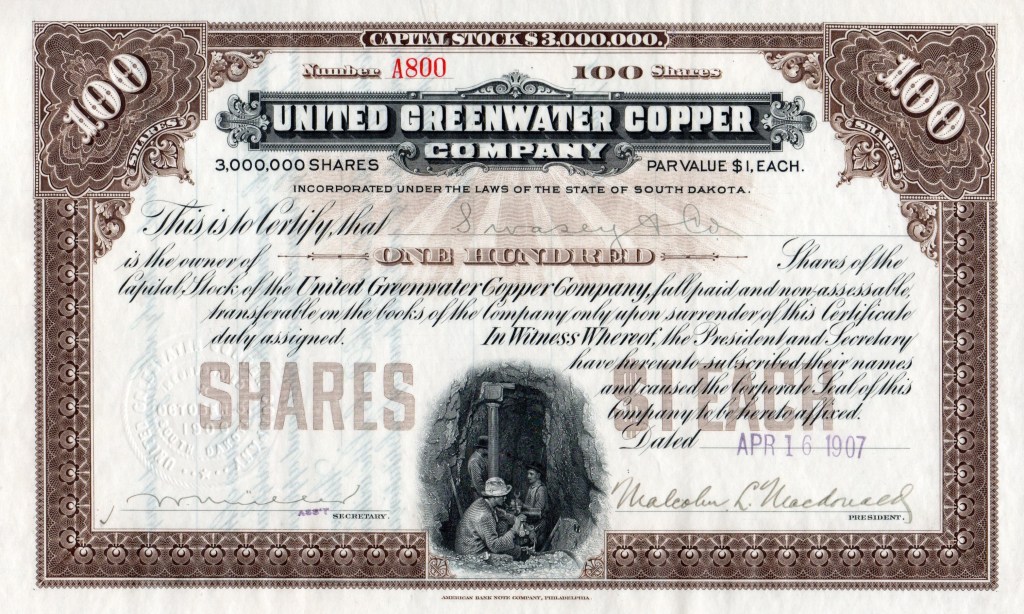

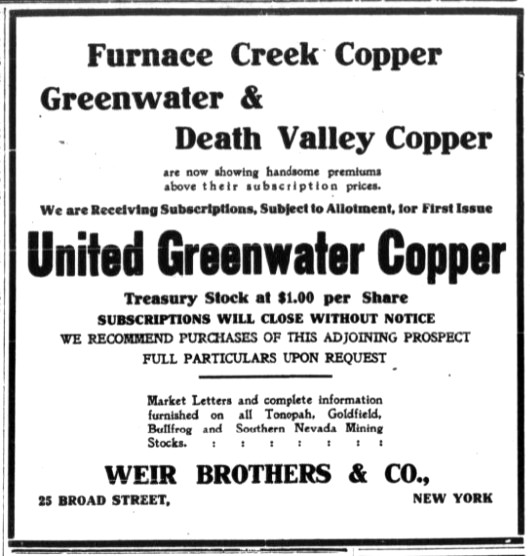

United Greenwater Copper Company

Certificate No. 911, One Hundred Shares to H. F. Collins, October 12, 1906. W. L. Carden, Secretary; Malcolm L. Macdonald, President.

Certificate No. A800, One Hundred Shares to Swasey & Co., April 16, 1907. [Illegible], Asst. Secretary; Malcolm L. Macdonald, President.

The United Greenwater Copper Company was organized by Malcolm Macdonald to operate 15 claims on the eastern extension of the claims of the Charles Schwab’s Greenwater & Death Valley Copper Company. From the start, United Greenwater was to be subsidiary of the Macdonald’s Nevada Smelting and Mines Corporation.

United Greenwater survived the Greenwater bust as late as 1915 through its ownership of claims near Amboy in San Bernardino County, California, and in Nye and Esmeralda Counties, Nevada.

Advertisement, The Sun (New York), October 8, 1906.

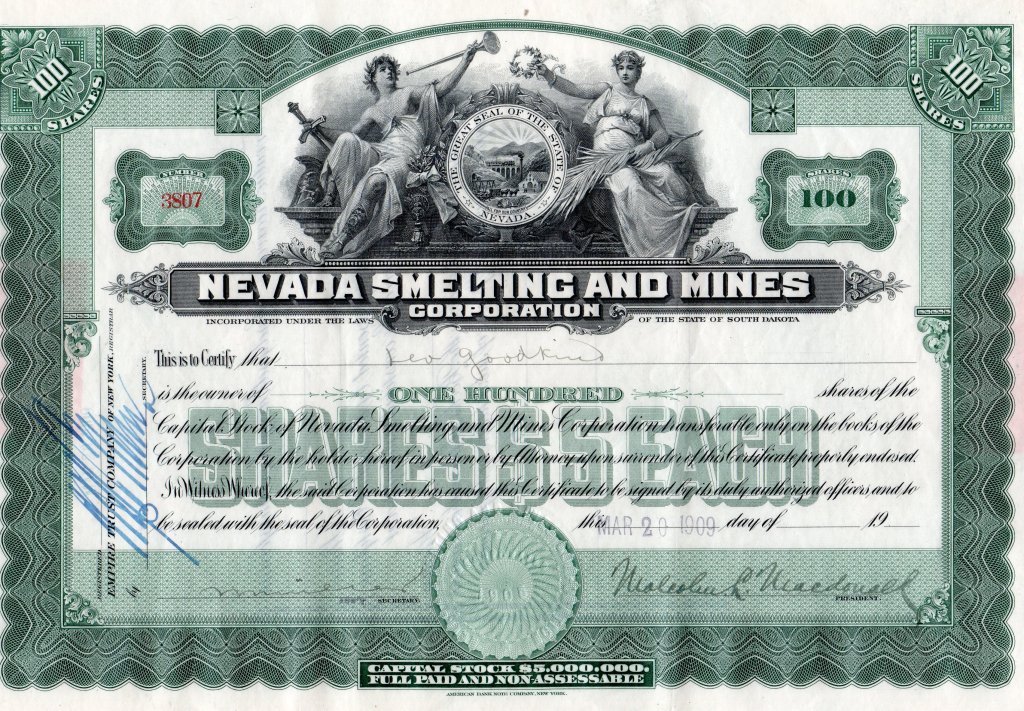

Nevada Smelting and Mines Corporation

Nevada Smelting and Mines Corporation, Certificate No. 3807, One Hundred Shares to Leo Goodkind, March 20, 1909. [Illegible], Secretary; Malcolm L. Macdonald, President.

Nevada Smelting was essentially a holding company, organized in June 1906, by Malcolm Macdonald, to construct a smelter to process ore from its copper mines at Greenwater, and gold claims at Kawich, Reveille and elsewhere in Nevada. The company owned or controlled eleven separate properties, aggregating 108 gold, silver and lead claims.

The smelter was never constructed. The Copper Handbook of 1909 reported that the company’s mines were, “idle.”

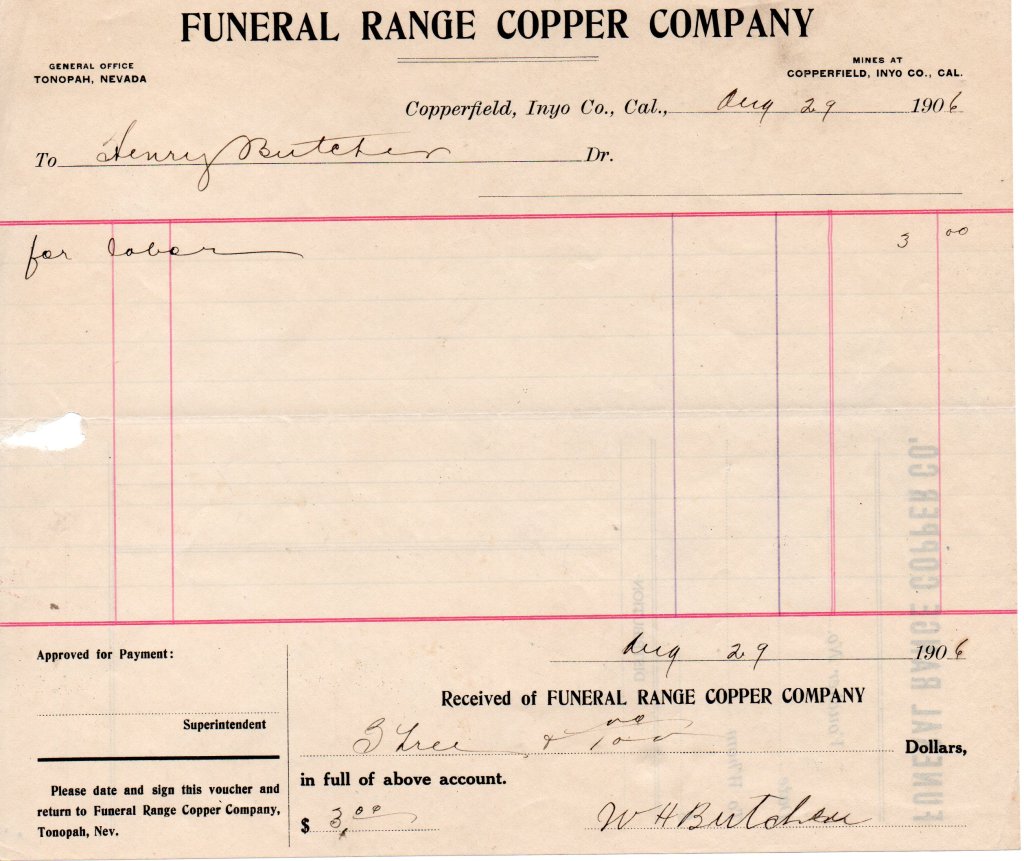

Funeral Range Copper Company

Payment Voucher for Labor, Issued to W. Henry Butcher, August 29, 1906.

Sometimes, a Greenwater mining company’s history is so fleeting, that any printed item, serves as tangible proof that some activity occurred. In this case Mr. Butcher was paid for some unspecified labor by the Funeral Range Copper Company.

The Funeral Range Copper Company was incorporated in 1906. The officers were well known in the district, including Donald Gillies, Arthur Kunze and John Salisbury. The company’s holdings were the Grand Central group of six claims that adjoined the United Greenwater properties.

Charles Schwab, the steel magnate who had been attracted to the Tonopah and Goldfield booms, was known to have held a minority interest in the Funeral Range Copper Company for a brief time in 1906, but sold out when was unable to gain outright control.

The Greenwater district had several competing townsites, including one promoted by Harry Ramsey. Ramsey insisted on naming his townsite “Greenwater,” although it was commonly called “Ramsey,” and less commonly called “Copperfield.” The Funeral Range Copper Company adopted the “Copperfield, Inyo Co., Cal.” as its seat of operations, as seen on the voucher.

By March 1907, the Funeral Range Copper Company had ceased operations and “folded up it’s tent” and heard from no more.

Advertisement including the Funeral Range Copper Company.

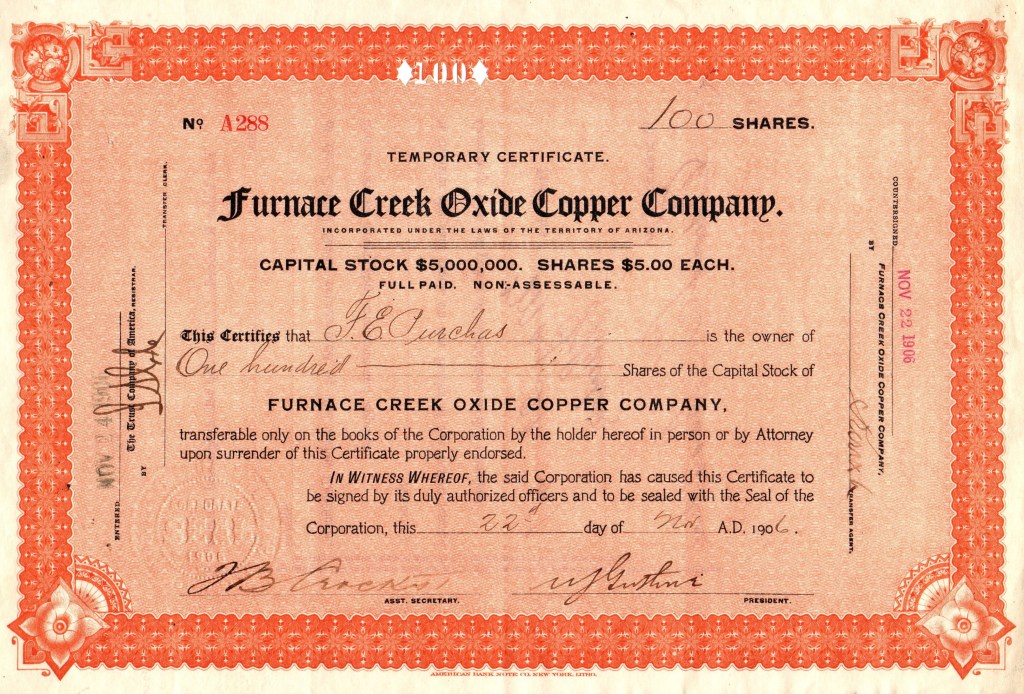

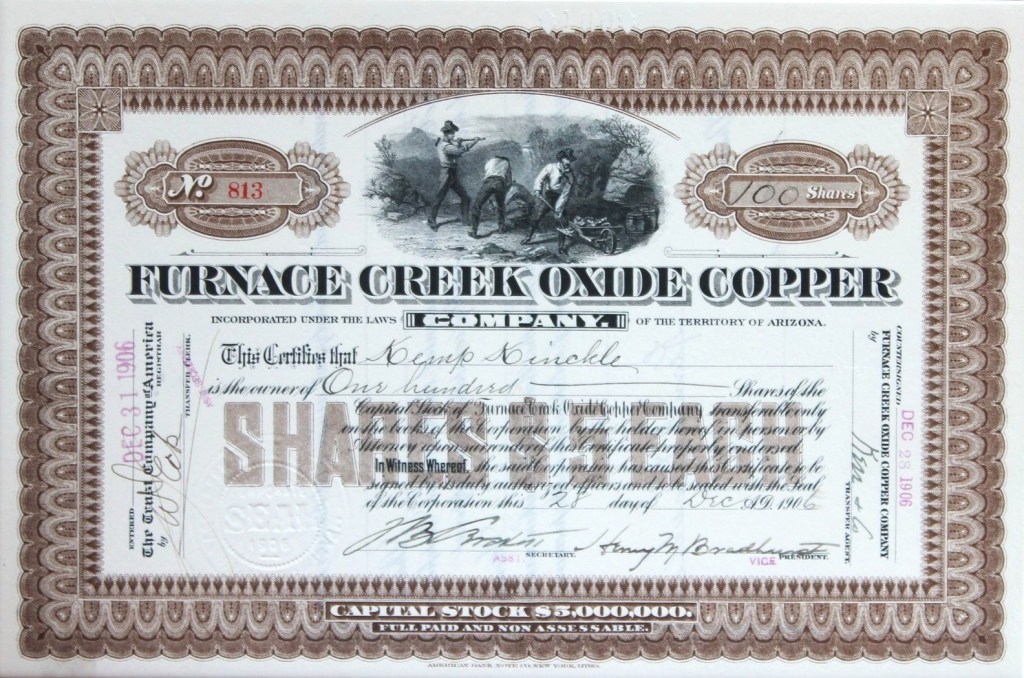

Furnace Creek Oxide Copper Company

Temporary Certificate No. A288, One Hundred Shares to F. E. Purchas, November 22, 1906. J. B. Crockett, Asst. Secretary, W. J. Guthrie, President.*

Certificate No. 36, Two Hundred Fifty Shares to F. A. Smith, November 2, 1906. John E. Corette, Secretary; A. J. Huneke, Vice President.

Certificate No. 813, One Hundred Shares to Kemp Kinckle, December 28, 1906, J. E. Corette, Secretary; Henry M. Broadhurst, Vice President.

The Furnace Creek Oxide Copper Company was organized by mining operators out of Butte, Montana. The company held six claims east of the Furnace Creek Copper Co., with a one hundred foot shaft showing copper staining. “Idle,” according to The Copper Handbook of 1909. However, F. C. Oxide survived, at least into the early 1920s, as a holding company for several producing Butte copper mines.

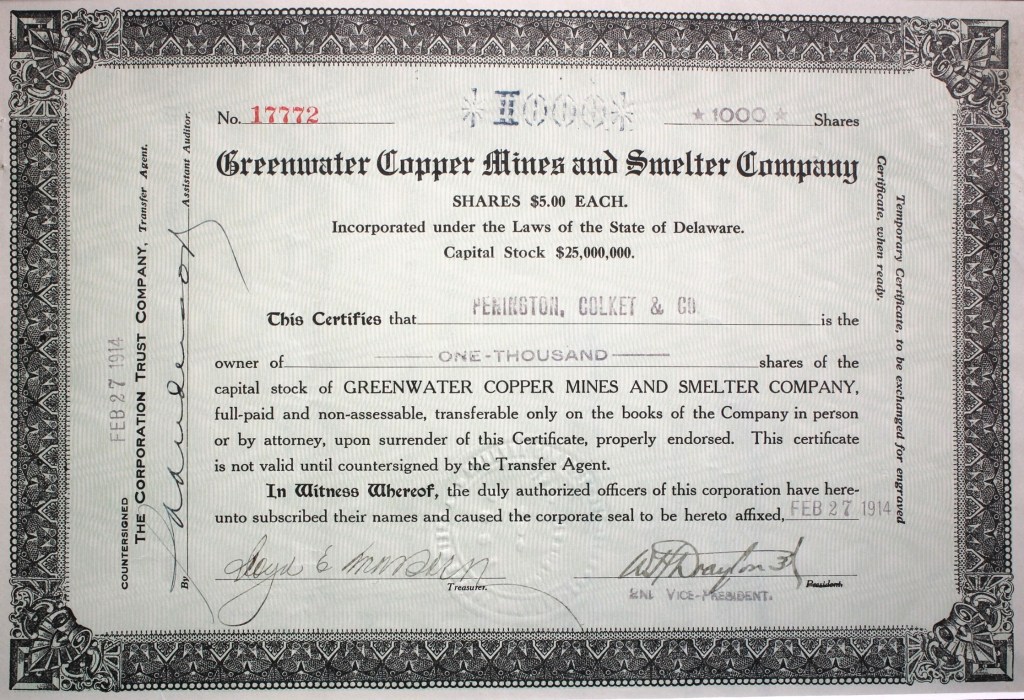

Greenwater Copper Mines and Smelter Company

Certificate No. 17772, One Thousand Shares to Penington, Colket & Co., February 28, 1914. Lloyd E. Marsden, Treasurer; W. H. (Hayward) Drayton, 3rd., 2nd Vice President.

The Greenwater Copper Mines & Smelter Company was incorporated in December 1906, as a holding company. The company owned practically the entire capital stock of the Greenwater & Death Valley Copper Company, the United Greenwater Copper Company, the Governor Greenwater Copper Company, the El Capital Copper Mining Company, the Iron Clad Greenwater Copper Company, and the Eagle Mountain Water Company.

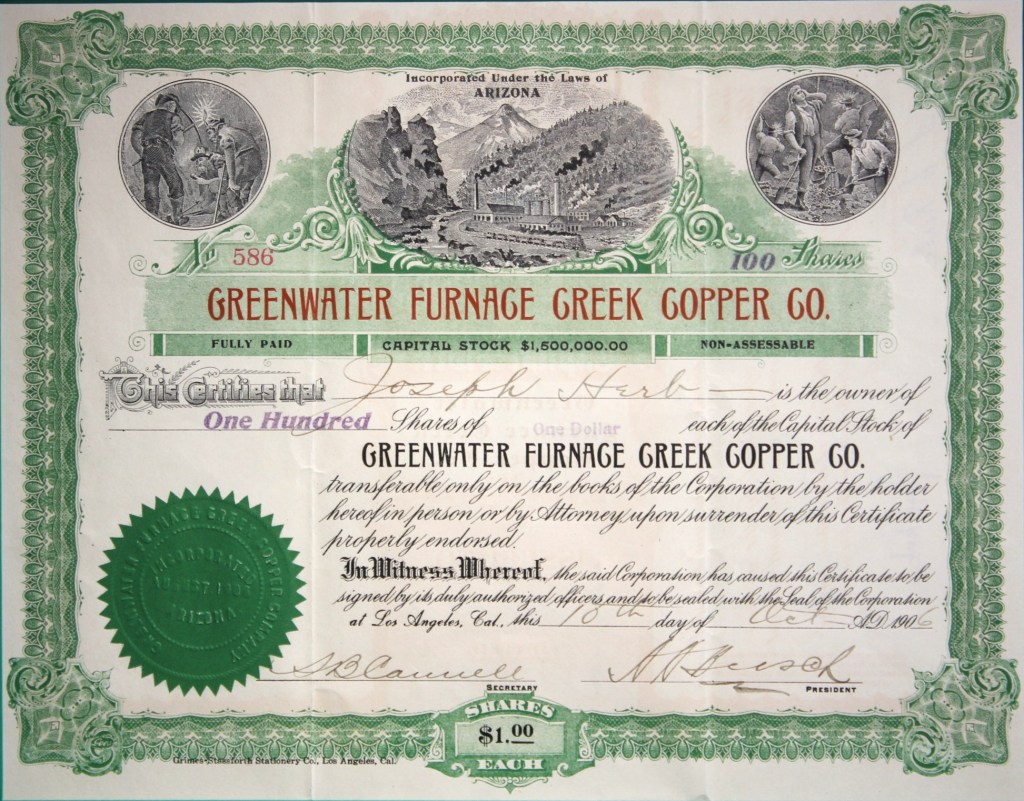

Greenwater Furnace Creek Copper Company

Certificate No. 586, One Hundred Shares to Joseph Herb, October 10, 1906; S. E. Cannell, Secretary, A. H. Busch, President.

“Letter returned unclaimed from former office, 219 Citizens National Bank Bldg., Los Angeles, Cal. Mine office: Greenwater, Inyo Co., Cal.,” reported The Copper Handbook of 1909. The company had 21 claims, 6 fractional, in an area of 375 acres, in the eastern part of the Greenwater district.

Although Greenwater Furnace Creek boasted of reserves of $5.2 billion of copper ore, an Army Major as mine manager, a United States senator as vice-president, and more copper than all the developed copper mines in the world, its mail was being returned.

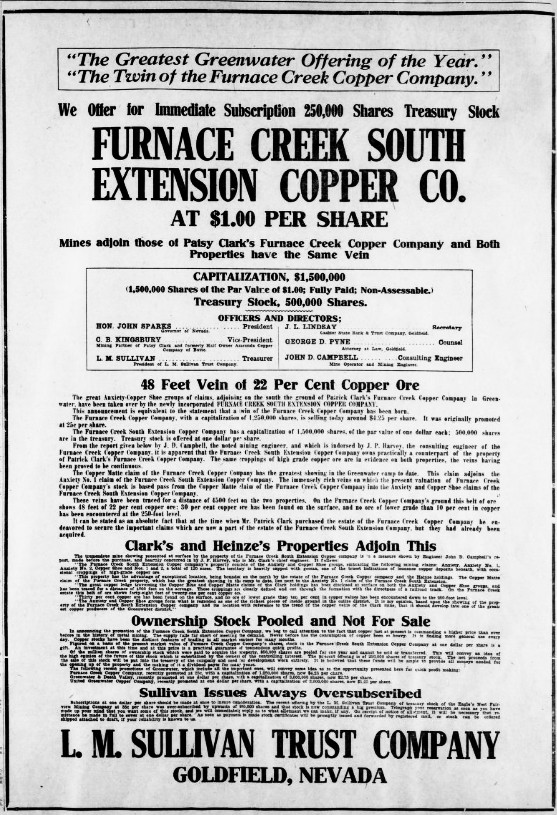

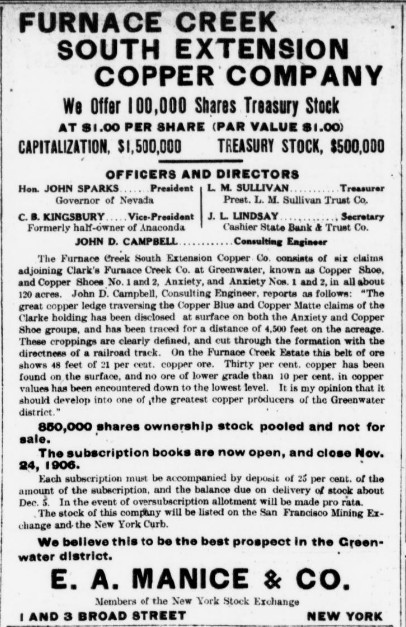

Furnace Creek South Extension Copper Company

Certificate No. 1709. One Hundred Shares to O. F. Jonasson & Co., December 3, 1907. J. R. Elgan (?), Secretary; Alexander Russell, 2nd Vice President.

According to The Copper Handbook of 1908, “Promotion by Shanghai Larry Sullivan, was marked by peculiar methods, though such methods are by no means peculiar to Sullivan. Is not regarded as favorable. Idle and apparently moribund.”

Advertisement, Salt Lake Herald, November 6, 1906.

Advertisement, The (New York) Sun, November 12, 1906.

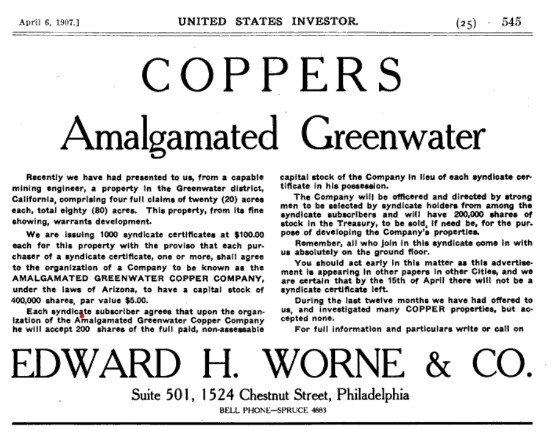

Amalgamated Greenwater Copper Company

Certificate No. 20, One Hundred Shares to Blanche Todd, October 23, 1907. Thos. B Headly, Secretary; Edward H. House, President.

According to The Copper Handbook of 1909, “Letter returned unclaimed from former main office, Greenwater, Inyo Co., Cal. Was promoted by Edward H. Worne & Co., who organizing a syndicate, with intention of incorporating later, on 4 claims, said to be in the Greenwater district. Apparently somewhat diaphanous.”

Advertisement, United States Investor, April 6, 1907.

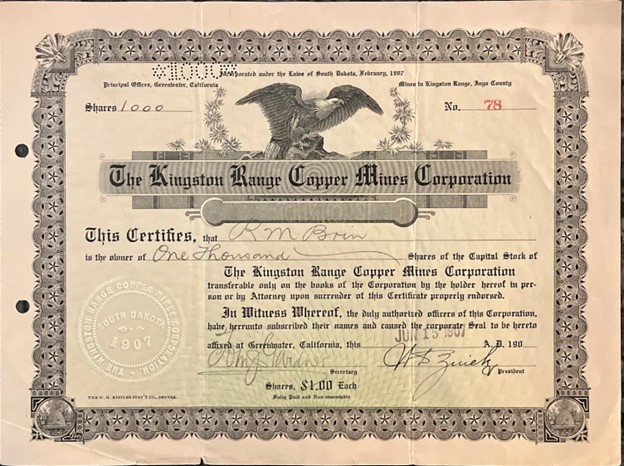

Kingston Range Copper Mines Corporation

Certificate No. 78, One Thousand Shares to R. M. Brin, June 15, 1907; Tom J. Gardner, Secretary, W. B. Zurich, Vice President.

The Kingston Range Copper Mines Corporation was an unusual Greenwater company. The corporation’s office was in Greenwater, but the mines were in the Kingston Range, as noted on the certificate. Measuring the distance to Kingston Peak, the range is about 28 miles southeast of Greenwater.

According to a report in March 1907, edition of the Salt Lake Herald, the Kingston copper deposits were discovered by Charley McCarthy and a “Dr. Ford.” The Kingston mines’ were described as 500 acres “adjacent” to Greenwater.

An advertisement in the April 1, 1907, edition of the Death Valley Chuck-Walla magazine, noted that the Kingston Range Copper Mines comprised twenty-four claims of the McCarthy Strike. The company’s stock was promoted by Kunze Investment Company in Greenwater. The shares’ owner, R. M. Brim, was a partner in Brin & Bernstein’s general merchandise store in Greenwater.

Kingston Range Copper achieved notoriety, not as a copper producer, but as the subject of a well-reported, high stakes poker game in Greenwater in May 1907. The San Jose Mercury-News (and other California newspapers) reported:

“600 excited spectators, mining operators and employees of the various mines in this section crowded around a table In the Greenwater Saloon last night. C. J McCarty [possibly mine discoverer Charley McCarthy], a mine owner and Patrick Hogan, owner of 460,000 shares in the great Kingston Range Copper Company. played stud poker for stock in a copper find that was worth nearly a half million dollars on the Boston exchange yesterday. As the secretary of the company stood by, book in hand, and wrote out the certificates of stock, Hogan was slowly reduced from great wealth to pauperism.

“The game started slowly, but soon grew speedy until the stock certificates passed entirely to the ownership of Hogan. It was a game for blood from the start, and money against the stock went every time. As fast as one of the crisp certificates was either won or lost, the secretary, who was present, made the transfer upon the books of the corporation. The company Is one the best in the Kingston range, and it is rich in both gold and silver, not taking into consideration that it Is one of the principal mines from which the new Ash Meadow smelter company expects to gain Its first supply of ore to start on.

“McCarty is the same man who a month ago won a saloon here on the toss of a dice. Hogan obtained a job as a driller in the mine of which he was formerly the principal owner.”

In the end, Greenwater fizzled out, no smelter was built in Ash Meadows, and there were no newspaper reports of copper wealth mined by the Kingston Range Copper Mines Corporation from the namesake mountains.

Advertisement, Death Valley Chuck-Walla, June 1907.