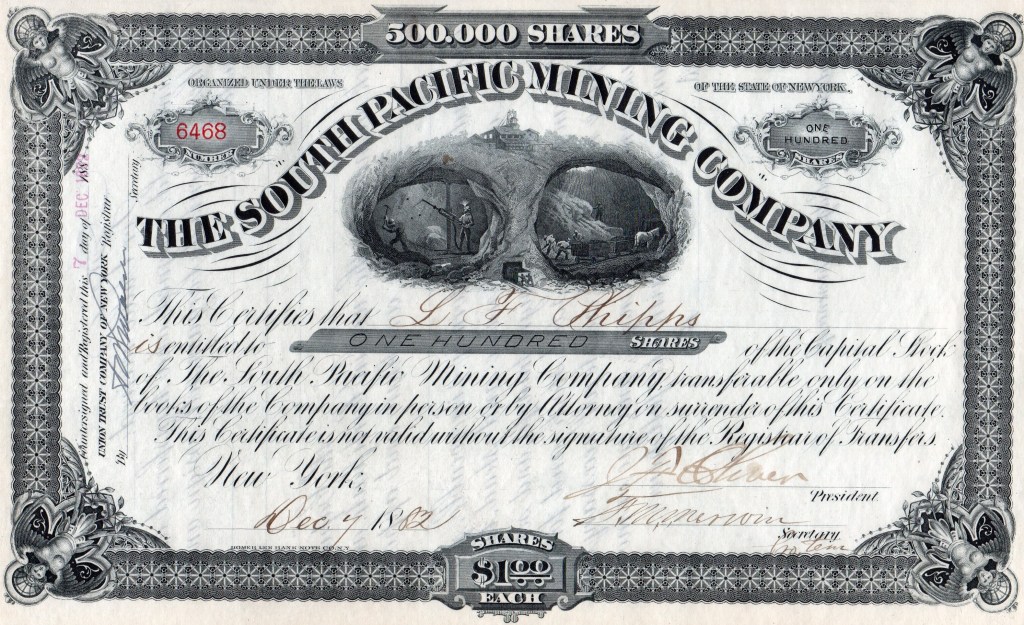

The South Pacific Mining Company

and

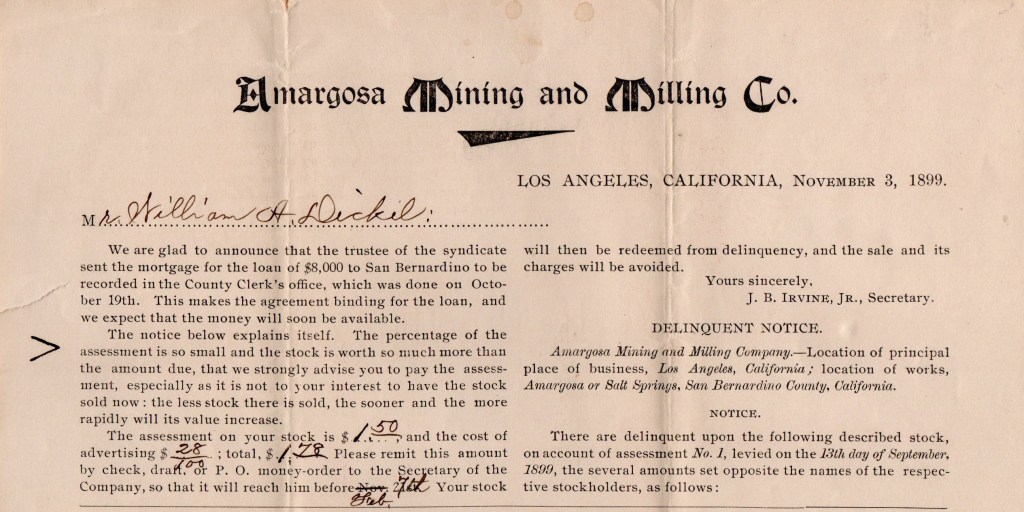

Amargosa Mining and Milling Company

Certificate No. 6468, One Hundred Shares to L. F. Phipps, December 4, 1882. J. A. Baker, President; [Illegible], Secretary, Pro Tem.

Certificate No. 690, Five Hundred Shares to William H. Grebe, December 27, 1897. James B. Hurin, Secretary; H. B. Eakins, Vice President.

Located at the extreme southern end of Death Valley near Salt Spring and the Salt Spring Hills, the history of the mine of the Amargosa Mining and Milling Company traces back to the travails of the Death Valley ‘49ers.

Jefferson Hunt was leading a group of ‘49ers along the Old Spanish Trail in today’s southern Nevada, including two Mormon missionaries, James. S. Brown and Addison Pratt. Brown and Pratt had experience in the California goldfields in 1848, having worked for John Marshall at Sutter’s Mill during the gold discovery. When it came to gold prospecting, they were the only two of Hunt’s group that knew what to look for.

On the afternoon of December 1, 1849, Hunt turned the wagons south from the Amargosa riverbed toward Salt Spring, which lay just beyond a low rocky point. Hunt and four companions, including Brown and Pratt rode ahead to check the spring where they planned to camp, taking a shortcut through a notch in the rocks. Pratt noticed bits of loose quartz and suggested that there might be gold nearby. At that they all started searching. Soon several flakes of gold were found in the sand. Then they found a 4-inch quartz vein with several pea-sized grains of gold. The men hurried over to Salt Spring, a mile ahead, where the wagons were already gathering. The discovery caused quite a stir, as several of the argonauts scrambled back to the spot and chipped some gold from the vein. However, they still had miles to go to reach Los Angeles Pueblo. When Hunt gave the call to move on the next day, the would-be miners reluctantly fell in with the train. The first gold had been found in Death Valley!

Hunt’s wagon train reached Isaac Williams’s ranch at Chino, Calif. on December 22nd and spread the word of the gold discovery. In January 1850, Williams led the first expedition back up the trail to investigate. They brought back more rich rock and reported a “whole mountain just like it!”

Upon reaching Los Angeles the travelers’ nuggets created more excitement. Benjamin D. “Don Benito” Wilson, Los Angeles’s first mayor, organized the Salt Spring or Margose Mining Company and fitted out a second expedition in February 1850 to open the mine. But they soon found that the distance and expense of mining at Salt Spring would not pay.

The first work to get rich off the Salt Spring Hills gold discovery was made by James Madison Seymour and his South Pacific Mining Company fraud in 1881. For that saga, we refer you to our discussion of the South Pacific stock certificate.

The Amargosa Mining and Milling Company was incorporated on February 27, 1897, by a group of Los Angeles men, including our certificate signers, Hurin and Eakins. The company was established to conduct mining operations at “Amargosa or Salt Spring, San Bernardino County.” On the stock certificate, take notice of the language, “Fully paid and non-assessable in accordance with the By-Laws.”

The By-Laws must have contained a loophole, exploited by the company’s board of directors. In September 1899, the board levied an assessment of one-fifth of a cent per share – payable in gold coin. Assuming a fully subscribed issuance (no stock held in the company treasury) the assessment would have raised $2,000. The funds, or some fraction thereof, must have been enough to keep the company going for a few more years.

In 1905, a stockholder inquired of the United States Investor regarding the status of the company. This magazine invited readers’ questions as to the value and viability of their stock investments. The magazine noted that the mine had been worked for at least 50 years, but the “original workings were not done in a scientific manner, and were more in the nature of ‘gophering,’ and as a result the mine caved-in some few years ago.” But management had kept up with legally required assessment work, a new road was being constructed to the mine, a 5‑stamp mill was onsite, and $10 ore was blocked out.

Alas, in 1912 the company appeared on the California Secretary of State’s list of corporations whose charters had been forfeited for non-payment of taxes. If the company had been successful, we likely would have more information between 1905 and its 1912 demise.

Amargosa Mining and Milling Co., Notice of Assessment to Stockholder William H. Dickel, November 3, 1899.

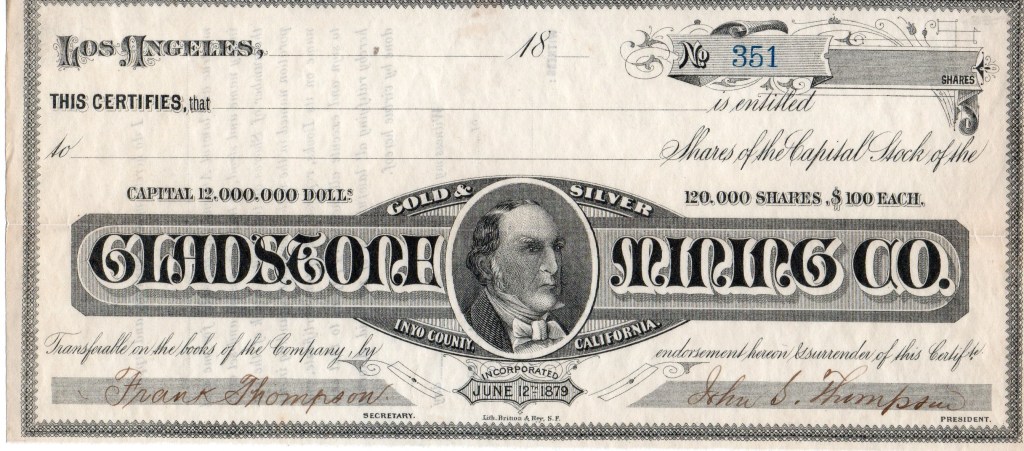

Gladstone Gold and Silver Mines Company

Certificate No. 351, Unissued. John S. Thompson, President; Frank Thompson, Secretary.

In the Mineral Basin District, just across the Amargosa River, to the west of Resting Spring, Barton O’Dair had a claim called the Vulture. O’Dair had opened the mine with financial aid from Los Angeles attorney and city councilman John S. Thompson, among others. When they found the ore wouldn’t pay, they decided to look for a buyer back east. They found just the man in Amasa C. Kasson, a Milwaukee sewing machine salesman. Together they organized the Gladstone Gold and Silver Mining Company on June 12, 1879, with $12 million in stock for sale.

Talking fancifully of a water-powered, sixty-stamp mill on the Amargosa River, a bullion production of nearly $2 million a year, enough ore to run for twenty years, insured dividends, and very limited offers of bargain-priced stock, Thompson sold Kasson’s Milwaukee acquaintances a sizable share in the paper dream. He also sold the postal authorities on establishing a post office at the paper town of Kasson, southwest of Tecopa. He also sold map maker Rand McNally on putting the town into their new Indexed Atlas of the World. The post office was abolished within a few months, when word got back to Washington that there was, “not a soul living within twenty-five miles of the place.” The Milwaukee investors were only a little slower in learning that they too had been sold a worthless mine. But the ghost town of Kasson haunted Rand McNally maps for more than a decade.

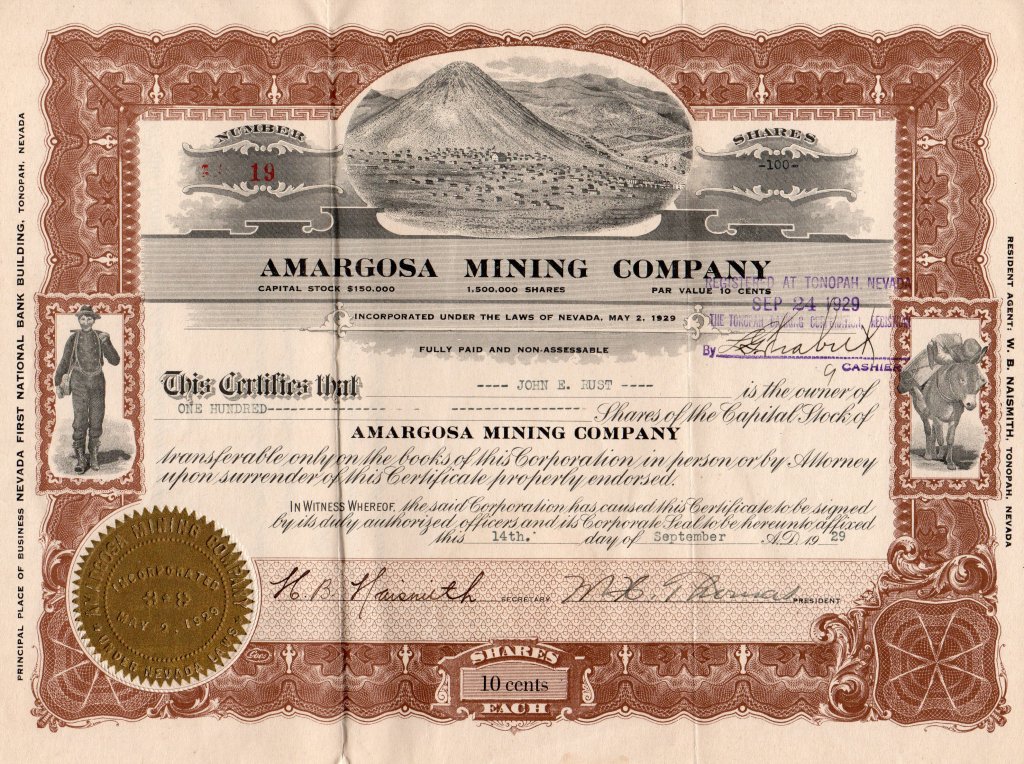

Amargosa Mining Company

Certificate No. 19, One Hundred Shares to John E. Rust, September 14, 1929. W. B. Naismith, Secretary; M. B. Thomas, President.

We could locate neither newspaper nor book references with information about the Amargosa Mining Company. However, we did learn that the company officers Naismith and Thomas, were mining men in western Nevada. Between the two of them, they were active from 1908 into the early 1950s.

As indicated on the stock certificate, the Amargosa Mining Company was incorporated in Nevada on May 2, 1929. Four months later, the Dow Jones Industrial Average peaked for the year. Amargosa Mining was not exactly a blue-chip stock and Mr. Rust purchased his 100 shares on September 14, perhaps around the par value of ten cents per share.

On September 8, 1929, financial expert Roger Babson predicted that “a crash is coming, and it may be terrific.” The subsequent market decline during September was termed the “Babson Break.” But it was on “Black Thursday,” October 24, 1929, that the stock market lost 11% of its value. October 28, “Black Monday,” saw stocks slide another 12.82%, followed by “Black Tuesday,” losing another 11.7%. As they say, timing is everything. The Great Depression was at hand. It’s likely that John Rust lost a $10 investment in the company.