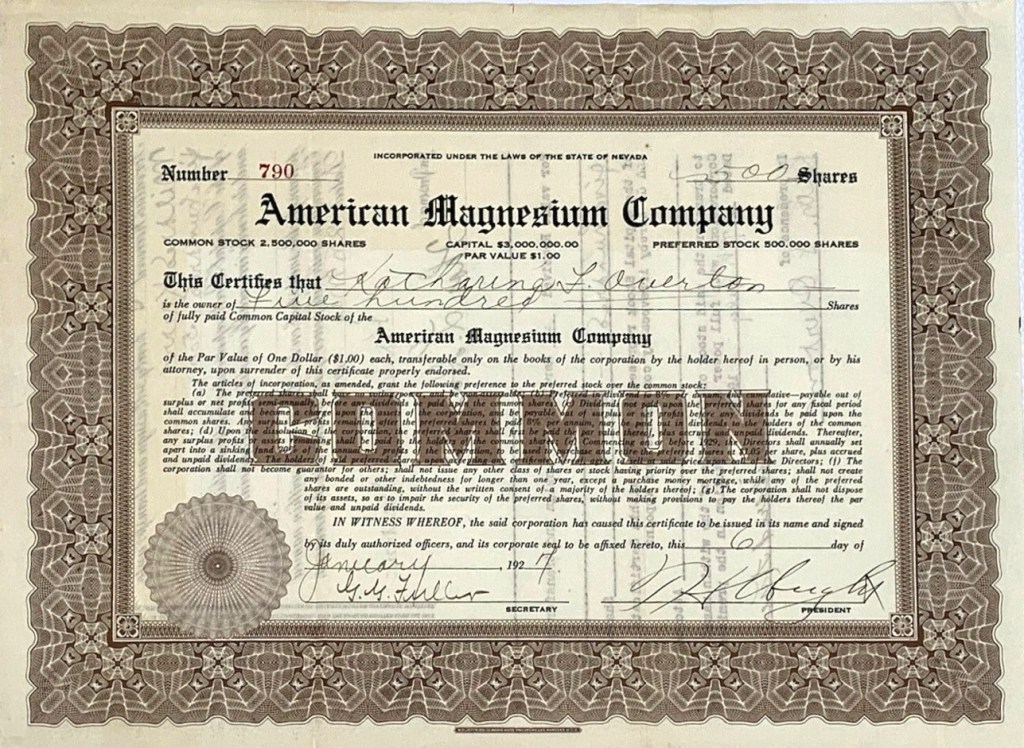

American Magnesium Company

Certificate No. 790, Five Hundred Shares to Katharine F. Overton, January 6, 1927. G. G. Fuller, Secretary; T. (Thomas) H. Wright, President.

A salt deposit was discovered in the Owls Head Mountains, south-southwest of Death Valley, during the fall of 1917 by Jasper Stanley and two other amateur prospectors from Los Angeles. What they found was alum, potassium aluminum sulfate. They staked nine placer claims, but the remoteness of the find prohibited any development.

Two years later, an acquaintance of Stanley, Los Angeles florist Thomas H. Wright, found that the deposit was richer in magnesium sulfate, commonly known as Epsom salt. Wright purchased a controlling interest in the claims and organized the American Magnesium Company. Wright determined that the only economic way to move the ore was by railroad – but not by standard- or narrow-gauge trackage, but rather by construction of a monorail system.

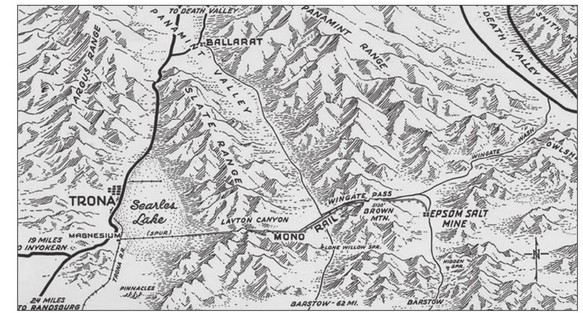

Work on the monorail began in the fall of 1922, beginning at the Magnesium rail siding on the Trona Railroad, six miles south of Trona, California, in Searles Valley. The line ran east across the south end of Searles Lake, up Layton Canyon and over the Slate Range, across the Panamint Valley, through Wingate Pass, and on to the salt deposit, named Crystal Camp.

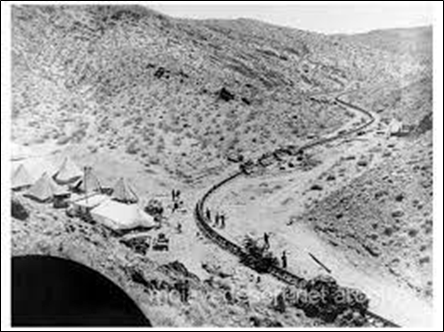

The 28-mile monorail was a single steel rail set on top of a 6-inch by 8-inch riding beam supported on a lumber “A” frame. An “A” frame had to be placed every 8-feet, and wooden guide rails were nailed to the bottom of the legs of the “A’s”.

The specially designed locomotives, which were converted Fordson tractors, and cars, ran on two wheels, with steel outriggers hanging down the sides. They rode like pack saddles astride the track with carefully balanced cargo strapped low on both sides. Construction took almost two years and cost about $200,000.

For two years, American Magnesium mined and transported magnesium sulfate via the monorail to Magnesium siding, and then on to Wilmington, California, near Los Angeles Harbor for refining. However, by 1925, the quality of the ore shipped was declining. In the winter of 1927, mining ceased. During the 1940s, portions of the mineral deposits, as well as the monorail line, were incorporated within the lands of the U.S. Naval Air Weapons Station at China Lake.

According to author Alexander K. Rogers, in the 2014 edition of his book, The Epsom Salts Monorail, the system’s right-of-way still exists, as do some of the “A” frame structures, mostly on the Naval Station land. Fencing and signs warning of severe consequences for trespassers dissuade scavengers scouting for pieces of the monorail.

Map of the Monorail Route and Mine Location.

The Monorail in Layton Canyon.

Locomotive and Work Car.

Monorail Locomotive and Car Transporting Workers and Supplies.